Shadows of the absent body

Judith Butler

I am most pleased and honored to be here today in order to reflect with you on the work of Doris Salcedo.1 The exhibition here at the Harvard Art Museum includes a number of pieces that inhabit and transform the space of the museum. What is it that the museum houses when it exhibits the work of Doris Salcedo? The museum provides walls and floors, entries and exits, even guards who know and defend against the desire to touch. In fact, in this exhibition there is a great deal of empty space as we encounter objects arranged on one side of the floor or sparely pinned on the wall. Of course, on one level these objects are exhibited to see, to approach, to walk next to, to kneel before, and then to leave behind – the departure from the room is surely part of the extended event itself. We all arrive and leave, but how quickly and how fully do any of us leave behind what we have seen? In the same way that we are perhaps compelled to ask, in what way does this exhibition transform the space of the museum, we also find ourselves in the midst of another problem: in what sense, if any, is this an exhibition? I don’t mean to indulge in hyper-reflexivity by asking such a question. But it matters whether we are coming to see art or to mourn a set of losses, or to do both, whether we are practicing mourning at a distance, whether this is finally an exhibition, a counter-monumental memorial, or a testimonial. For the fact is that we wade through loss as we enter, watch, approach, discern the materials, stop ourselves from touching or sitting or treating them as if they were part of a living architecture or an object that carries over seamlessly into ordinary worlds. The exhibition includes the entry and exit of these living bodies who we are, the empty room, or the partially empty room, the spatial encounter with an arrangement of objects which once could have had a function in ordinary life and now no longer do, objects whose loss of function signifies the loss of a world, an inhabitable world.

Indeed, in every space we are confronted with the problem of inhabitation and the uninhabitable. These objects bear resemblance to those that could have once belonged to someone. In what sense, if any, are they inhabited still by those who are gone? Those who are gone are precisely those who were dispossessed and vanquished, those who were killed and lost in a flash or in waves, those who remain nameless within the exhibition precisely because oblivion is washing over the names or because no record was ever firmly established. The exhibition is a memorial, not only counter-monumental in kind, but manifesting the power of oblivion, exposing, if not indicting, the loss of testimony or acknowledgment, a loss that can be neither fully known nor fully mourned. The word has very little place in these rooms. Who once spoke? Who speaks now? It seems that the objects have become the representatives of the vanquished bodies, gathered as if in a contorted assembly, a set of chairs gone awry where a meeting once was or could have been or should still be. That sort of temporal variation structures the object field. Where did the bodies go? This is, of course, the haunting question left by the disappeared. Who is left to ask the question and to hear it? Is it the objects that give testimony and, if so, how do they do it, through what form? And what else do these objects, taken together, give and do?

First let us try to answer to at least one of the demands of this exhibition, which is to remember or recall a violence that is at risk of being effaced by the overwhelming force of oblivion. The assaults on the conditions of possibility of a complete record come from various sides. The record was never kept, the record was only partially kept, the record did not serve as a basis for prosecution, the record is now supposed to become history rather than a law case, demanding reparation. And yet, quite apart from the language of law and the failure of public records, the task of mourning persists, and so repair too takes on another meaning. What does it mean to mourn when those who are lost cannot be fully reconstituted in thought or image? It is not clear in how many ways oblivion does its job, so obstructing its force is no easy matter. Yet, we can militate against it here by considering the social and political history of destruction that forms the background of this work, and then move to a consideration of these objects and these spaces, or, rather, allow these objects to have their way with us as they make their claim.

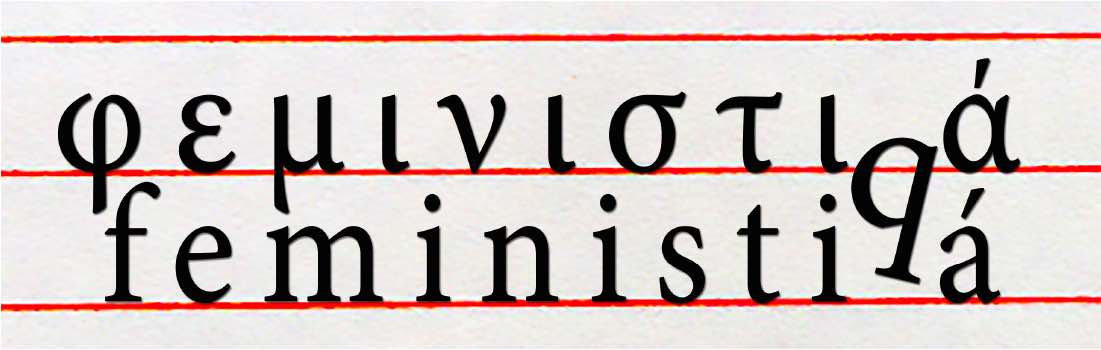

As you may know, Colombia has undergone enormous violence in the 20th and 21st century. In the Fall of 2016, a peace accord was reached between the government of Juan Manuel Santos with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (or FARC), or, rather, their representatives in Havana, that mandates the cessation of violence on all sides, the break-up of the FARC camps, and facilitates their re-entry into civilian life. The final deal dispensed with a Truth Commission and sets up conditions for Colombian judges to hear cases. In the meantime, FARC has become a political party. That agreement is sealed, but it is called into question intermittently. It was rejected once before finally passing because some conservative parts of the population worried that it would introduce gender equality as one of its stipulations (and hence, the “gender ideology” which has become the ever intensifying target of evangelo-fascists throughout Latin America and elsewhere). After final ratification, new killings have certainly taken place, but the deal has significantly ameliorated the conflict. Indeed, there is nothing that precludes the possibility that new groups will seek to gain control of areas now vacated by FARC. Indeed, the ELN has grown since the dismantling of FARC, and their conflict with the government continues; peace talks between them were severed in February and began again in May. The outcome is unclear. They remain amassed on the border with Venezuela, and have not yet agreed to end their violent activities that have included assassination, kidnapping and hostage-taking of government officials, landowners, and corporate leaders. So, we are here asked to consider a form of violence that has a history, but one that continues in the present as well, and whose future form we do not know.

In the late 1940s, political conflict broke out between the two major parties in Colombia, the Liberals and Conservatives, and what followed was sustained violence that, within sixteen years, claimed the lives of as many as 200,000 people. We should perhaps pause at that statistic simply because as I sought to read about this, I was struck by the different estimates. There seemed to be no reliable measure for counting. Some say the number could be as low as 80,000, and some say more than 200,000, so how is that to be determined? I will return to this problem of numbers shortly. That protracted period of partisan warfare was called “La Violencia,” starting in 1946 in which Conservatives who owned land and monopolized wealth sought to oppose and disenfranchise Liberals who sought land re-distribution and the end to rural poverty and destitution. When the Liberals were officially banned by a Conservative party that had become dictatorial [and that does happen, and not only in Latin America], and when Jorge Eliecer Gaitán, the leader of a left populist party that sought to represent the needs of the poor, was assassinated in 1948, riots broke out in Bogotá: a violent political struggle ensued that lasted until 1958. A non-violent left party gave way to violent splinter groups, and in 1950, “La Violencia” became a state-sponsored campaign, with most of the brutal violence taking place in rural areas. In 1962, the US helped to develop a counter-insurgency plan for Colombia, seeking to strengthen the paramilitary forces as they sought to oppose communism in the countryside. In 1964, left opposition groups were once again outlawed by the state, which gave rise to several guerrilla groups, who used violent means, including assassination, kidnapping, and extortion, against corporate figures and local officials. The ensuing period of violence is only now coming to an end or into a different form. In the so-called “drug-wars” that began in the late 1970s and that led to escalating paramilitary and guerrilla warfare in the 1990s, more than 50,000 people were killed.

So, throughout the political spectrum, one finds those who both suffer and inflict violence. Human Rights Watch in Colombia reports that FARC and ELN inflicted enormous violence, and that successor groups to paramilitaries have also emerged in recent years that have wreaked destruction throughout the land. About thirteen years ago, right-wing paramilitary groups emerged in the aftermath of an official paramilitary de-mobilization. This armed conflict forcibly displaced 6.8 million people, “generating the world’s second largest population of internally displaced persons (IDPs) after Syria.” During this period, tens of thousands have also disappeared. I can hardly give a full account of this violence, and the inability to give a full account is surely part of my theme this evening. But it is worth emphasizing the violence perpetrated by many different parties: FARC, ELN, the new and old paramilitary groups, or indeed the state-sponsored army brigades and security forces. Further, from 2002-2008, it was the army brigades and security forces who regularly killed civilians in an effort to “show positive result and boost body counts” (HRW) – they needed to bring back those numbers to those in power as proof that they were doing their job of exterminating the left. We will see how well the present treaty holds (the Nobel Commission surely lent support to the treaty in awarding the peace prize this year to Santos who made use of that occasion to condemn the “war against drugs” – not because there should be drugs, but because the history of that US-backed policy became the instrument through which paramilitary violence escalated in rural communities, and because the legalization of drugs would put many killers out of a job – many of the guerrilla groups trafficked in drugs to finance their own operations, especially after they lost whatever international support they had because of their violent methods). Of course, there are many sides to this conflict, and the inadequacy of any account will be part of what I want to reflect upon this evening. But my task is not to lay blame – even though there is much blame to place on all sides. Important for us, however, is to note that this last period of violence is one of the most important historical contexts for understanding Salcedo’s work, the violence to which it responds, and the losses it seeks to bring forth through exhibitions that are tellingly deprived of any human form. There is no human in any of these exhibitions, and yet the massive loss of human life is the structuring absence of every scene.

As we approach the work of Doris Salcedo in this moment, in the immediate aftermath of this treaty –a time of tentative hope–, it is important to register another violence that continues. If we consider feminicidio, that is, the murder of women, including trans women, the statistics still stagger: a woman is killed every other day in Colombia. This statistic firmly secures a minimum understanding of reality, but how many unreported deaths are there, and if they were reported, how would the numbers change? Indeed, so many of these statistics of violent death in Colombia are based only on registered and recorded documents, efforts to grasp how many and when, since especially in the past, but still now, the reporting systems are hardly reliable. Why go to the police with a report if you fear the violence of the police? How do you go to the police when they are not always distinguishable from the security militias who have done the killing? The need to establish the facts is a legal and political necessity; we will return later to the question of forensics, and the political demand for evidence. We can say that facts are facts, and there is a great deal that is reassuring about such a claim in light of the US administration’s skeptical relation to facts, its failure to remember facts, and its propagation of alternative facts. But for those who investigate crimes against humanity, it is a truism that a fact has to be established as such in order for it to be recognized, and that means that the assertion of a human rights abuse has to rely on established facts, has to establish the facts, and that this is a political requirement in order to make a judgment.

But judgment is not exactly our task right now, even though reading the political history of Colombia brings about many very clear judgments. The testimonial in a law case is different from the one enacted by a work of art. In the work of Doris Salcedo, however, establishing the facts of death is necessary to undertake a process of mourning. But the inverse is also true: mourning is one way to come to terms with the reality of loss, one way to establish the fact itself. The process of mourning is one in which initial disbelief is followed by a series of reality-verdicts. Freud uses that legal term to describe the process of mourning: we are effectively engaged in an internal trial with our own scenes of loss, submitting evidence to ourselves, admitting or refusing evidence delivered by reality as well as the final verdict that the loss has, indeed, taken place. Loss cannot be felt without the acknowledgment of loss. So, for Freud, the loss of life can be refused and disallowed by the living, but in those cases, the living lose touch with reality, refusing its verdict, as if they do not live within the jurisdiction of death, or that it does not matter what evidence is submitted to the senses. The melancholic ether that results from such a refusal is one in which there remains a dim and equivocal understanding that someone has died, or that many have died; that acknowledgment is thwarted by a suspension of belief, sometimes fully undercut by overt denial, and sometimes simply normalized as the way of the world.

In any case, melancholia partners with oblivion: these are facts I will not know. To take such a stance is already in some sense to know what one wishes not to know. So, perhaps the formulation is different: these are facts I will not know that I know. This means that in relation to loss I am the kind of being who can suspend or deny what it knows until some unequivocal verdict from reality arrives. For Freud, the evidence of loss has to be introduced to the melancholic psyche bit by bit: a case has to be made over time; the world has to be re-encountered time and again as the world that no longer houses that person or, indeed, an entire population. In the case of mass death perpetrated over many decades, in the cases of so many deaths that never were fully counted, that appear now to be countless, innumerable, if not supernumerary, how does a work of art take form such that the reality can be acknowledged? It is not only in a court of law that the facts of death must be established, but in the court of the mind as well. The fact of loss is delivered to the senses, but in melancholia it is the senses that have closed to that fact, refusing to admit any facts of this kind, and so traded a sense of historical reality for a provisionally functional oblivion. How is it possible to establish as a set of facts countless deaths, deaths denied by absent or destroyed records, deaths cloaked by the ether of cultural and political melancholia, so that these deaths can be mourned or, at least, become eligible for mourning?

We may think that numbers have no place in such an endeavor, but that is not true. Even if we know that not all of the dead can be counted, that we are left fathoming the countless, it is most important nevertheless to count, and to affirm and strengthen the statistical records. In a book entitled Counting the Dead: The Culture and Politics of Human Rights Activism in Colombia, Winifred Tate takes up the phrase “contando muertos,” used to characterize the tireless and repetitive labor undertaken by human rights activists of counting the dead. Sometimes the phrase is dismissive: is that all human rights workers can do? But this process, she points out, is not just about counting how many died, but also of making the dead count. So making the dead count is not exactly the same as counting the dead. Making them count means making them matter, giving their lives value, establishing them as lives worth grieving. And we can add, in light of Salcedo’s work: making them matter means trying to find and shape those materials that can establish how and why these bodies should matter. So already, we see that being counted, being valued, and taking a material form are bound together in this situation when the dead are counted but not all the dead can possibly be counted, and when the records are fragile or absent or destroyed, and when the question of the value of life, of life that has been lost, remains both urgent and unanswered.

In what ways, then, is it possible to count, to make count, to make matter, the numerable and innumerable dead? To make them count means to represent the persistently vexed problem of violent death in relation to the problem of number, of fact, the materiality of a loss that is defined by its absence from the material world. The open and relatively unanswerable question of how many died turns into the question of how to establish those deaths as mattering, and how to give material form to those deaths so that they do matter. This last is a different kind of act of accountability. “Contando muertos” names the indispensable work of establishing the record of violent death, a record of crimes against humanity, yet that counting cannot alone establish the criminality of the killing, nor can it by itself give value to those lost lives: counting is not the same as the act of mourning. After all, if we are speaking about the loss of a life, of many lives, then we are speaking about that whose value is incalculable. Even as we have to count the living and the dead, we cannot arrive at the value of the living or the dead through any counting we do. Counting can never account for the value of those lost lives. For that another mode of accountability is necessary, one that registers loss at the level of the senses, one that links the tasks of art with the labor of mourning.

We will turn to that in a moment, but first, let us conclude our discussion of numbers and counting, for it leads us precisely to the problem of what it means to seek to represent an incalculable loss. For Jacques Derrida, the effort to do justice involves a relation to what is incalculable, which is one reason why justice and accountability are not the same.2 He calls justice “a calculation within the incalculable.” Perhaps this is a better way to understand “contando muertos”. Because the demand for justice is singular and absolute, there is nothing to which it can be rightly compared – it is beyond the measure of comparison. If we do compare the justice of one decision with another, we have in mind some measure that may help us adjudicate that comparison, but the measure itself cannot be compared to any other. In a move that, incidentally, mirrors Kant’s transition away from the mathematical and toward the dynamic sublime within the Critique of Judgment (which is his work on aesthetics, aesthetic judgment in particular), Derrida makes clear that no specific instance of justice, say the existence of a just law or a just treaty, can fully stand for justice. Indeed, there is an asymmetry between justice and any of the laws that come to be called just; whatever justice may be, it goes beyond the distinction between instance and general rule. It is not that there is a Platonic ideal of justice, but only that the demand it makes upon us is absolute and singular. So when we call for justice, we call for something that is unequivocal, that does not equivocate, which is why justice is never found in a perfectly satisfactory way. It names an unqualified demand and a striving without end, one that cannot be fully translated into deeds and words. Indeed, for Derrida, the demand of justice cannot be reduced to a set of clearly articulated norms, a position that put him at odds with many contemporary political philosophers. It is not as if there can be no norms, no norms that are just, but what makes them just will itself not be a norm.

My own view is that we can formulate norms to think about both equality and the value of a life, that help us to illuminate why within a mediated public sphere some lives are very grievable and other lives, less so. Although we may think that we are only speaking about populations that are lost when we refer to a grievable population, grievability and ungrievability characterize the living. If and when a population is grievable, they would be grieved if they were lost, and they bear and know that hypothetical in life: if they suffered a violent death, that loss would be unacceptable, wrong, an occasion of shock and outrage. Grievability is a characteristic attributed to a group of people, perhaps a population by some group or community, or within the terms of a discourse, or within the terms of a policy or institution. That attribution can happen through many different media and with variable force – it can also fail to happen, or happen only intermittently and inconsistently, depending on the context, depending as well on how the context shifts. But my point is that people can be grieved only when they bear the attribute of grievability. If a life is no life to begin with, or if a life loses its right to life by virtue of being demeaned or dismissed a living best, then the negation of life precedes the loss or life, and that loss can be neither acknowledged nor mourned under those conditions. A violence of one sort has preceded a violence of another. And so, acknowledging a loss when there are no established conditions for its acknowledgment can break through the melancholic norm – that is, I would suggest, activating the performative dimension of public grieving that seeks to expose and oppose the violent limits imposed upon grievability and to forge new terms of acknowledgment, new occasions for mourning. This would be a form of militant grieving that breaks into public space and time, inaugurating a new constellation of space and time, a new constellation of the senses.

How, then, to forge new terms of acknowledgment? Without a norm that establishes the equal grievability of all lives, we can understand neither mass killing nor the destruction of evidence nor the indifference to the evidence that exists. Although the pursuit of justice and the act of mourning are not the same, one problem that pertains to justice pertains to the concept of grievability as well. Both are, strictly speaking, incalculable (the loss is incalculable, but so too the abrogation of justice). Considered from both a semantic and normative perspective, no form of calculation can by itself yield justice; no form of calculation establishes a lost live as worthy of grief or lets us know how to mourn. For justice and for the task of mourning, the loss has to be somehow established, that is, given material form. But where forensics discovers evidence to establish loss, mourning must find and make its own material – the wooden plank, the disfigured chair, the blouse that bears the endless duplication of a shaving or a shard.

The risk of nihilism is high: so many people died on all sides of this political conflict, this ongoing and resurgent civil war, how can anyone go about mourning the loss or even objecting to the injustice? And yet, Salcedo’s work takes up the task of mourning in the face of its apparent impossibility. The task of mourning under such conditions is something other than establishing the public record, preparing the testimonial narrative. Salcedo’s task is not the same as that of the historian who must establish the conditions, the causes, the fact of violent death. And yet, she is establishing the death without always having a record; she is making that record with the objects she has. It is here not a matter of giving an account or telling a story: the mass killing has to be figured in another way, through a double act of memorialization and testimony, a form of mourning that does not seek to suppress the violence that has taken place, but installs it indirectly yet forcefully at the center of the scene. The objects in this exhibition do not tell a story: they exhibit a condensed or impossible narrative, a story that has not been told and may well not be tell-able. The loss, the violence, the forgetting are given at once, amassed together, congealed in the objects, fact-objects, as it were, that bear the incalculable.

So this last problem is one that links forensics, art, and human rights: how to make the number of deaths matter when we do not, and cannot, know the full number, when number alone cannot establish the reality, the value of those lives lost, or tell us how to undertake the task of mourning. That paradox has to be materialized in some form; it has to give, and be given, value. The losses that form the background and the objects of this exhibition cannot be fully counted; when the historical record is lost or effaced, when the losses become countless, then a different kind of mathematics comes into play: a replication of marks that are too small to count, the duplication of marks on a dress or blouse that turn out to be shards of metal, the repetition of detail that could extend indefinitely, the open-ended character of a pattern. They seem to be the same mark, but there is some variation in the midst of the open-ended sequence. For the most part, however, the object is the material condensation of the countless, bearing the incalculable.

Let us then turn to the work of Doris Salcedo to understand how this works. First, I would note that even the single room in the museum, whose entrance establishes the failure of any protective enclosure, is at once that room and any number of rooms emptied of those who once inhabited them, now not just empty, but structurally uninhabitable. From the start we are spatially caught up in an allegory of loss. It is one space, but condenses a replication of spaces where inhabitation no longer happens. Of course, none of us live in the rooms that the museum offers. The museum is the space where no one lives, locking us out at night, a negative space of the domicile. And yet here, in this exhibition, the specific un-inhabitability of the room takes form, ghosted with killing and vanishing, as we walk or move through the space. Are we registering a history as we move, or are we moving through a bit more quickly than we intended, forgetting what we see as we leave the room behind, secure in our sense that we are the living and implicitly the grievable ones? What moves through us as we move, and what stills us when we stop? Nothing finally holds or keeps us in any of those rooms – we can exit at any time. So something of our own freedom is also at play, and so implicated in what we see. The room is neither a prison nor a mortuary; neither is it really a house, though it carries the remnants of the house – indeed, more a space than a room, or a room that is not quite a room, for no one inhabits that space. On the one hand, that is a more or less ordinary fact of museum spaces – people do not live there. On the other hand, the un-inhabitability structures the scene, the traces of a home are arranged in such a way that they constitute an uninhabitable structure, and this is what is exhibited, what finds and stops us in the act of moving through, raising the question of our freedom not to stay, not to see and not to know. Do we refuse the loss, let it become part of the blurred history of violence in another country, one in which our own government played a pernicious role, or do we let ourselves be claimed by what we see?

#1 Untitled

#1 UntitledI am suggesting that none of the traces of a human habitat come together in a way that is inhabitable in this exhibition. No human body can fit inside those boards and slats, even as the structure resembles a tomb. Even the dead body could not reside there. Is it that these structures are emptied of bodies, or is it that the structure has become one way of giving materiality to the absent body, the one that never received the proper burial? We could ask the question in an even more straightforward way: in what sense does the object ensemble we encounter represent the absent body or absent bodies? If the body is not inside, where has it gone? The dense composite of useless or abandoned furniture becomes a kind of tomb that houses no body, refiguring the memorial function in a counter-monumental way; these are ordinary elements of the household that are no longer functional, stacked into a tomb-like structure that cannot serve its purpose. And yet, if this is in some sense a tomb, it is one that lets us know that there is no tomb, no memorial, only a makeshift structure that takes the place of both body and tomb. A scene of contrivance in the midst of a loss that will never be fully fathomable, what I am calling a tomb is layered: the workspace on top of an old dinner table where people surely once gathered, maybe a desk on which people once wrote, maybe one of these slats was once a busy breakfast table and an ambient sense of belonging, a visual palimpsest of ordinary life, vacated and soundless. The furniture is stacked in such a way that there is no hollow space inside, no room for air, no more room to breathe. All of these objects are on one side of the room, and then there is all that empty space for aimless wandering where even the remains do not remain. That seems to be the space of vanishing, of disappearance.

#2 Untitled (detail)

#2 Untitled (detail)One reason we cannot settle on the memorial function of this set of objects is that they also exhibit the absent body in a way that does not redeem the loss by making the body present or alive again; they also conduct the very violence and destruction we are asked to register. So, if in some sense the furniture is suffocated and suffocating producing a density with no internal room, it is precisely because the structure manifests both the killing and the memorial function at the same time. I will suggest that this happens time and again in this exhibition. This structure, untitled, nameless, houses no skeleton, no remain, but is itself the density of an absent body, the negation of a cavity where air might flow. So it is and is not the body itself at the same time that it is and is not the memorial for that body, at the same time that it is and is not the violence – the taking away of a body’s breath and mass – to which it also attests. There is a stacking of wood and concrete and steel, all of which bring weight and density into the scene where a body once was. Something is piling up, not unlike the stacking of bodies in mass death, not unlike the memorial that never was for those bodies whose exact number remains unknown, whose vanishing leaves no trace. In such cases, the trace has to be crafted.

#3 “Thou-less”

#3 “Thou-less”And what about those chairs, the challenged verticality of all those chairs? No human form can settle into these chairs. No chair has a back. The vertical post might be likened to a spike, and perhaps there we also see how that object replaces and recalls the human limb, torn from its torso, but also the instrument of violence itself. In 2002-2008, when army brigades were asked to show proof that they had killed guerrillas, they killed them, placed weapons on their lifeless bodies, and then reported them as enemy combatants killed in action (HRW, World Report). Those reports and images made it seem that those they killed had been engaged in battle even though they had been sought out and killed precisely when they were defenseless. The weapon became a perverse tombstone on that occasion. The vertical marker is also at once the echo of both the weapon and the tombstone, but this memorial does not establish the place where the dead are buried. It stands for the place that is no place. The chairs lean this way and that much like stones in a cemetery that has suffered the brunt of bad weather for years. And yet something menacing emerges in the midst of the household structure. What of the war dead who are too numerous and nameless for a tomb? Some force has ripped through these chairs, and yet something awkward, violent, and useless still stands, muter than any object was ever supposed to be. Is this the force of deadly violence or the harsh wind of oblivion? For what does it mean to make a memorial for those for whom there is no complete record? Is the problem that the evidence has not been found, or is the problem that forgetfulness is more compelling than knowing what happened, where and when? If forgetfulness promises a quick return to ordinary life, Salcedo’s art reminds us of the haunting distortions within the ordinary, ones from which there seems to be no easy escape.

One expects that all these works of art will be wrought from found material, but throughout these exhibitions Salcedo has gathered wood and metal and fabric to produce and reproduce the objects that take the place of those lost lives. That contrivance is an open secret, establishing the act of making as part of the practice of mourning. This is yet another way that mourning distinguishes itself from both law and justice. In the work “thou-less” there is an empty space at the center of the room. There is no you, no “thou” in the sense that Martin Buber intended. The “thou” in his work is the one I address, the one who also makes an ethical claim on me, the one with whom I enter into a relation that is at once human and spiritual. In Buber, “the thou” is a person and not an object. For a person not to be an object, one has to be in an ethical relation to that person. The “thou” is thus the one with whom I share a reciprocal relationship, a living relation. In this work, the relation is broken, and we are left with the “it” – the object that the human was never supposed to be; but this object is –and is not– the absent body: it is animated by that loss, a material extension of lost life. This is not a simple case of the other treated as an instrument and an object, and an ethical requirement to restore the human form by the memorial. No such restoration is possible. And the impossibility of any such restoration is in some ways the point or mourning: those lives are really gone, and they are not coming back. If it were possible, we might expect portraiture or narrative to re-humanize the loss. But there are no human faces here, only the remains that are inhabited by a lost form. But perhaps Buber got the object wrong. The “it” that remains is animated precisely by the human body that is lost, which is why the objects conduct the testimonial, re-enacting the scene, the violence, shadowing forth the body. In some ways, the objects are the animated shadows of the body; the fold of the one resides in the fold of the other. So there is perhaps something both living and sacred that now emanates from the object itself at the same time that each of these objects emblematizes the violent instrument that took life away. The sacred was supposed to be between two humans, for Buber, precisely what kept both of them ever from becoming the “it”, the dehumanized object. But perhaps Buber had not considered the animated object, or the way that absent space can point to the permanently missing body.

#4 Disremembered

#4 Disremembered“Disremembered,” three sculptures made of woven, small silk, crafted between 2014 and 2016, is based on conversations that Doris Salcedo had with women in Chicago who had lost their children to gun violence. Perhaps these hanging clothes belong to the grieving mothers, or perhaps they are simply blouses emptied of the human form by which they could be filled out. Who or what has become disembodied in the scene of grief? Has the mother lost her own body as she lost the child? The clothing, now limp, vacated of the human form, seems as if it was once filled out by a human body, a curve suggests that there is still some bodily inhabitation of the blouse. It is as if the curve of the body were still working the textile. In one, the right shoulder is raised, recalling a lilting human posture. The body seems to shadow forth when one sees the effect of density and opacity produced by the folds. But the opacity that only a body could provide is absent. The opacity of the material recalls the opacity of the body that it can neither replicate nor restore. We see this again in “A Flor de Piel,” where the rippled surface suggests an animated force having passed through, leaving the sense that this has all been lived in.

The garments are covered by 12,000 needles, sharp metal piercing instruments in miniature, replicated into patterns. The metal is confusing: are they a ghostly replication of gunshot – the regulated shavings of a bullet? Has something splattered here? They are so regulated and patterned, perhaps they are also standing for the dead, small tombstones in a regulated cemetery wrought of garments. Or perhaps these are smaller versions of the spike motif that we found in the chairs. Is the needle the instrument by which a garment is made, or is it the remnant of the violent instrument, reduced and multiplied as a pattern? Have the instrument for sewing and violent instrument now become bound together in the blouse, producing an ambiguity that does not resolve?

#5 Disremembered (detail)

#5 Disremembered (detail)Even the spike by which the blouse is mounted on the wall is part of the continuing problem of the instrument that can be used to harm but also to make and secure art objects. Enlarged and expanded, the needle becomes the knife or the bayonet: reduced and patterned, it displays the instrument that sews the garment itself. The work of art incorporates the violent instrument. But the object is also the vanished body and the living effect of that disappearance. The blouse is both transparent and pierced, hanging somewhere that is clearly no one’s house, hanging on an impersonal wall for a crowd of strangers to see. Alternately transparent and opaque, emptied and inhabited, it poses the question of whether this loss can be known, acknowledged, or mourned. It matters that there is one wall that is left empty and that is where full disappearance without a trace makes its absence known without the possibility of a materialization or, rather, where the wall is the only material, exhibiting the impossibility of exhibition within the exhibition itself.

The title: “Disremembered.” How does it come about that something or someone can become dis-remembered? Is it that something was remembered, but then disavowed? Is it that there has been an attack on memory, an effort to root it out? It is not simply that memory faded with time, or that some impersonal force of oblivion unleashed its powers on the memory of an historical record. The attack on memory is a continuation of the violence; and the compulsion to forget is thus a refusal to know and to mourn. Over and against that violence and that oblivion, Salcedo begins to sew and to weave.

#6 A Flor de Piel

#6 A Flor de PielWe see how much reparation is required when we grasp the 12,000 needles, or again in “A Flor de Piel” (2012), we come to understand the painstaking labor by which thousands of preserved rose petals, often assuming the color of dried blood, expand the garment across the floor. The title literally means “like the flower of skin”; it is a Spanish expression for an emotional outburst, sometimes a frenzy, but also for the dramatic exposure of the most sensitive layer of skin. It began as a memorial to a nurse who had been brutally killed in Colombia and whose body had never been found. The petals have been treated to keep them from fully dying, setting up an allegory for the work of art that appears in this light to be a process that suspends organic material between life and death. Is this what the artwork does, seeking to keep death and dispersion from reaching a conclusion in evanescence and oblivion? Even then, the folds attest to some exterior force, a wind or a substance, a body shrouded, that refuses to let that textile lay flat. The folds are without volume, but some force from elsewhere worked its way through this elaborate act of sewing and making. Although the artwork began as a funeral rite for someone who lacked one, each petal comes to stand for another victim, threading them together in the shroud. Once again, the material continues the lost materiality of the body under conditions where there is no continuation, bound up with the memorial, and the indictment. In this case, there is no sharp object, no longer thematized in this commemorative object. But there is a unity, even a solidarity among the petals, a negative assembly, a solidarity of a different set of organic materials that continues, and departs from, the bodies for which they stand, organic materials whose own passing can be only suspended, but never finally stopped.

How are we to understand, then, art in relation to the task of reparation? It will be neither a peace treaty nor a truth commission. But it will be an act of reparation, of what Salcedo called “knitting our own peace.” These are the words she used to describe her recent work called “Sumando Ausencias” (a title that could be translated as “adding up absences” implies a summing up, a form of tallying, taking place in a continuous present, an ongoing process), a memorial quilt that covered the entirety of Bolivar Square, and that represented 7% of the victims of war. This was the third of her installations in that square: in 2007, she created “Acción de Duelo” (“Grief Action”), covering the ground with nearly 24,000 lit candles. Aligned to form a neat and busy grid, the glowing dots commemorated the lives of the 11 murdered deputies of Colombia’s Valle del Cauca Department, kidnapped as hostages in 2002. On the one hand, there were those 11 brutally killed, but she links them with thousands more, producing a solidarity on the ground among flashes of light. “Sumando Ausencias” recalls the Names Project and the AIDS Memorial Quilt that began in 1987 and now comprises 48,000 panels commemorating those who have died of AIDS. On the other hand, this quilt is also a shroud, and the writing is covered over in part with ashes.

#7 Sumando Ausencias

#7 Sumando AusenciasWhile the panels of the AIDS Memorial Quilt included tokens of the life, memories, poems, the quilt that Salcedo installed this last Fall during the debates about the peace treaty were simply names, some of them fading or partially legible, covered by ash, but also in some sense turning to ash. Some of Salcedo’s long-time admirers in Colombia worried about foregrounding those losses during that time and in that way. The names were important as a way to counter the failure to remember and to mourn, but the artwork also documents the failure of memory, the current risk of forgetting, leaving each piece of the quilt with a name but no context and no history.3 Indeed, the artwork was itself evanescent, and so it proves also to be in vain, subject to the force that fades, the force of oblivion. Indeed, this lack of a fuller contextualization on each of the panels disturbed her critics, but the point, as I understood it, was precisely to show the invariably limited and fragile character of memory in the face of the imperative to mourn; the name could only be a scrap of the person torn from its world; its decontextualization is a minor monument to the violence of that condition of having been torn away from the living world. In some ways, the work was grand, even monumental –covering the public square, surrounding the statue of Simon Bolivar–, but it also distributes its memorial function in a spare and even way, avowing its limits, its inadequacy: one is once again up against the blank wall, since where are the 93% who could not be represented here? The work exhibits the limited and fading character of representation itself. If the demand of mourning is to acknowledge loss, to refuse disavowal and dissociation, then how does one go about acknowledging unfathomable loss through material means that are also evanescent?

In a news release commenting on “Sumando Ausencias,” Salcedo remarked, “The names are poorly written, almost erased, because we are already forgetting these violent deaths.” So the work marks not only what cannot be represented, but what is always at risk of never being represented. “We are already forgetting” seems to be another way of saying that we are “dis-remembering.” That, too, has to be part of that exhibition. It would be easier if we could simply say that Salcedo’s work counters the failure of memory. But no, it gives us that failure as well on the wall, on the ground, in the stitches that cannot put everything or everyone back together again, cannot even form a thought, an image, or an object or an arrangement of objects that reconstitute the losses that animate its material form. The public square is where we might expect an assembly of bodies who gather precisely to enunciate the popular will, to constitute themselves as a people. But in Grief Action or indeed in “Sumando Ausencias,” there are only candles, light, fabric, or ash, precisely where the people should be; so in a literal sense, the panels stand for the people who cannot stand there. Where one might expect an assembly, the embodiment of democracy, we find instead an assembly of the object world, countering oblivion and subject to transience. It is a fragile convocation that seeks to maintain the memory of the absent body in the object world rather than converting it into presence, an effect that would deny the absolute character of that loss as well as the absolute unjustifiability of that loss. There is nowhere an effort to make of art a route to redemption, for that would be as consoling as it would be false.

The object world houses that absence and becomes the material condition for its encounter. We may think that greater “visibility” is the ethical and political answer to those histories of atrocious loss that leave the dead nameless. But how is namelessness to be presented as part of the contemporary horizon of obliteration and persistence? Every act of “making visible” is haunted by what can no longer appear or, indeed, by lives whose living and dying did not register at the level of appearance. When making it all visible becomes the answer, a redemptive potential is invested in the field of vision. The problem is that the field of vision is disrupted by loss, for only some lives register within a field of vision that can be communicated across locality, nation, and hemisphere. The visible field is to some extent governed, we might say, by the persistent distinction between the grievable and the ungrievable, and the gradations between the two.

#8 Sumando Ausencias (detail)

#8 Sumando Ausencias (detail)If the task of mourning is to avow a loss, to refuse its denial or its censorship, then there must be a medium in which that avowal can take place. If we expect the senses to do the job, we may be alarmed to find that the visible and the audible field is already implicated in the differentials of grievability, distinguishing not only between those who are grievable and those who are not, but those whose grief is recognizable, and those whose grief is regarded as no grief at all. For who shows up as lost, as worthy of mourning, who does not first register as lost in some medium? Sometimes a loss is no loss precisely because there is no media to register that loss and in some sense there never was a life worth grieving. And when the legal and public records fail to register that loss, or when oblivion becomes state policy, to what media must one then turn to undertake the task of mourning? If the media is implicated in the problem, then which media is still possible both to exhibit and counter that disavowal? The materiality of the object marks the rupture with the materiality of the body through materiality forms the nexus in which they continue to be connected. These divergent and overlapping materialities – that of the body and that of the object – cross one another as different dimensions of a sensate world.

I have been suggesting that Salcedo’s work poses this fundamental question for us: through what materials can a material absence be marked and mourned? When that material absence is life, how is the living character of that loss passed through the material world of wood, nickel, silk, steel, the rose petal, cloth? On the one hand, the materiality connects the one and the other, perhaps most obviously in the case of the rose petal and the case of the ash. The one form of density cannot replace or reconstitute the other, and yet the intimacy of weight and fold, of density and volume, all pass through the materiality of the objects, and the objects, in turn, reconfigure each dimension of the scene: the killing instrument, the memorialization that never took place, the lost body, and the forgetting of the killing and the loss either because of a mandated oblivion (oblivion as state policy) or because of a refusal to mourn those who are considered ungrievable in any case. A single set of objects works in all these directions at the same time: memorial, testimony, the history of violence, the imperative to mourn.

For Salcedo, no one is ungrievable. Grievability is a potential that is only partially realized through a transformation of the object world, bringing forth the tactile relations of proximity, the shadows of the absent body that now take shape in the field of objects, in their folds and hinges. These are not remnants or remainders of a life, but objects that emerge precisely when and where there are no remainders; they assemble in new form, never giving back that life, but establishing counter-monumental forms of memorialization through forms of material density and replication that conjure an assembly of bodies, a mass protest from a place of death that is no grave. An assembly of objects takes the place of an assembly of bodies. For a loss to be acknowledged, a new form of materiality is required, not the materiality of the body, but one that can body forth its absence in a sensate domain. It would seem that when the body is no longer recoverable or recognizable, objects assemble to bespeak the loss. But in cases of violent death, the sharp instrument is either incorporated into the material of the memorial or radically subdued and refigured as the sewing needle, patiently and methodically countering the force of oblivion that would make mourning impossible. For Salcedo, we only become human by exercising the freedom and power to bury the dead. In this way, Antigone’s claim against her uncle who prohibited public mourning reverberates across the surface of this art. If we lose the capacity to mourn, to mourn in public, then we have lost something human: we are no longer the “thou” to whom anyone can direct an ethical address, or from whom one can be received.

In closing, let me tell you a story of listening to the families of the forty-three students who were “disappeared” in Ayotzinapa, Mexico, in September 2014. Those students were attending a rural teachers’ college, a leftist school that teaches them to teach young people in rural Mexico. They were about to board a bus to travel to Mexico City to honor a group of students who, in 1968, had been killed by government security forces when they sought to exercise their freedom of assembly and protest. So these students were also disappeared, but the local and national government refused to investigate, or they claimed to have investigated, but said that they could not find any remains. Witnesses claimed that the police had taken them, but the police said they had no idea where they are or what happened. The family and friends of those who were disappeared called upon forensic specialists in Argentina who, in the post-dictatorial years, have been seeking to unearth the evidence they need to establish the cause of death of those who were disappeared, and to allow whatever remains might exist to be given a proper burial. The government pointed to one patch of earth, but there were no bones, no traces of human bodies, so the parents continue to search, joining with other families, looking together for 700 of los desaparecidos, and the international group of forensic investigators checks every lead. The federal government is now meeting with the parents, and there may be some openings in this case in the future. But the parents have made a strong statement: they claim that they are not mourning, that they cannot yet mourn. And one of them remarked that she is not deluded, that she does not expect to find out that her child is still alive, but until there is evidence of that death, she is not grieving, she will not grieve, and she is waiting for her child to come home. She is not expecting that return, but she demands that return, and until the evidence appears, she will not grieve. This claim is one that has been made throughout Latin America directed toward governments that refuse to establish the record, to find the evidence, and to bring to justice those who have perpetrated such crimes.

She is not grieving, she says, though I see that her face is streaked with tears. She is saying that her right to grieve has not yet been honored, that she requires the evidence of that death, whatever form it takes, before she can grieve. She wants the dirt, the ash, the coat sleeve, the teeth, the bodily remains. Without that materiality, there is no mourning. Only when her rights are honored will her grief become possible. She is living the hell of the ungrievable. For all those whose claim to the right to grieve is never honored, Salcedo makes the mark that stands for that death and for all the others that remain unmarked, producing a solidarity of those who survive, but also, among the dead for whom the object speaks, articulating the claim to the right to be grieved by those who lost their human form and their human life, and require another material world to bear forth their claim to be publicly grieved. The objects establish grievability in a context where legal powers have failed, testifying to that failure, but also to the demand for grievability that exceeds the law, linking art to politics in a world where so many have vanished, and the record of their disappearance is at risk of vanishing as well. These objects do not tell a story nor do they give a full account; they bear the untellable, the incalculable in material form. They obstruct oblivion, and bear its force.