Arts of critique: An introduction

Elena Tzelepis

Because of your elite status from a year’s worth of travel, you have already settled into your window seat on United Airlines, when the girl and her mother arrive at your row. The girl, looking over at you, tells her mother, these are our seats, but this is not what I expected. The mother’s response is barely audible—I see, she says. I’ll sit in the middle.

Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (2014)

I invoke here Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, a book-length prose poem about everyday insidious racism in America, in order to register the critical force of public art and/as dissident poetics. By departing from, and reusing, the conventions of lyric poetry, along with visual texts and other artistic and digital media, Rankine recounts, in the second singular person, mind-numbing racist incidents and public encounters as they had been experienced and/or witnessed by herself or friends of hers. In so doing, she lets the autobiographical lyrical “I” be traversed by and interconnected with a multiplicity of voices, bodies, languages, memories, imageries, and experiences which have been displaced, disdained, marginalized, and obliterated by legacies of racial injustice and white supremacist imagination. This personal and/as political portrait of the present as ordinary acts of racist violence and injustice makes possible, and is made possible by, an inextricable interweaving—or, intimacy—of textual and visual poetry, fiction and nonfiction, essay and image, artist and audience, as well as critical race theory and antiracist art and aesthetics. It accounts for the intertwined political, sensorial, and aesthetic intensities by which citizenship’s embodiment becomes racially (un)marked. Here is how Rankine reflects on her intertextual aesthetic and curatorial agency: “The use of images in Citizen is meant in part to destabilize the text so both image and text would always have possibilities, both realized and unimagined by me, beyond my curating powers. Consequently, I wanted to create an aesthetic form for myself, where the text was trembling and doubling and wandering in its negotiation and renegotiation of the image, a form where the text’s stated claims and interests would reverberate off the included visuals” (as cited in Berlant, 2014).

Rankine’s meditation on Blackness, invisibility, and the body politic mobilizes poetry’s forms to recount the racial homelessness that founds normative assumptions of citizenship. This is my point of departure in this text: what happens when intertwined poiesis and thought witness how the injuries of injustice permeate the body politic, including the body, our bodies, and other bodies in/as public spaces; what happens when we start paying and calling attention to what has been rendered invisible and inaudible by forces of normative representability; and what happens when arts and acts of critique create spaces to engage with these questions, and to get disoriented by them even if—or, especially when—there is no easy answer on offer.

This collection stages the mutual implication of art and critique. It seeks to register critique as a possibility for a different attentiveness. The Foucauldian notion of critique introduces triggers of doubt into “truth regimes,” thus dismantling the authoritarian logic of their closed truths that pass as natural and self-evident (Foucault, 2001, p. 111–113). Critique in Foucault is located within the constellation of power, knowledge, discourse, and subjectivity. It refers to ideology and power relations that permeate dominant discourses masquerading as common sense. Normative discourses define what is normal and pathological. If thinking is the action that places a subject and an object in their various possible relations, then a critical history of thought in Foucault is an analysis of the conditions under which certain relations of subject and object are formed or modified, insofar as these relations constitute a possible knowledge (savoir). Foucault studies the “norms of power/knowledge,” which form the constitutive and non-queried elements of the present, what he calls the “ontology of the present” (Foucault, 1997). The ontological order of things is itself a naturalised result of historical and political processes (Butler and Athanasiou, 2013). Foucault seeks a way to enable the possibility of critique without reintroducing the transcendental subject as the presupposition of critique. And so, he questions not only the forms of absolute truths, but also the autonomy of the knowing subject that has been established within the history of western philosophy. He does not presuppose a subject’s position of authority that lies outside the realm of critique. In Foucault’s theorization, we are subject to authority and through our subjection to authority we become subjects. At the same time, however, we do not identify with the power that determines us. In fact, this is the unresolved ambivalence at the heart of subjectivation: how we question what allows us to exist as subjects (Butler, 1997).

Foucault’s notion of critique entails additionally a self-transformation of the subject as it ultimately amounts to her practice of resistance to the established norms. “‘Critique,’ he writes, ‘will be the art of voluntary insubordination, that of reflected intractability [l’indocilité réfléchie].’” (Butler, 2001). “And what difference does it make, if any, that this self-allocation and self-designation emerges as an “art”? asks Butler in her engagement with Foucault’s renderings on critique. She continues:

If it is an “art” in his sense, then critique will not be a single act, nor will it belong exclusively to a subjective domain, for it will be the stylized relation to the demand upon it. And the style will be critical to the extent that, as style, it is not fully determined in advance, it incorporates a contingency over time that marks the limits to the ordering capacity of the field in question. So the stylization of this “will” will produce a subject who is not readily knowable under the established rubric of truth. More radically, Foucault pronounces: “Critique would essentially insure the desubjugation [désassujetiisement] of the subject in the context [le jeu] of what we could call, in a word, the politics of truth.” (Butler, 2001, pp. 32, 39)

Style is constitutive of the ways critique is articulated and affects performative enactments of social desubjugation from normative power regimes and transformation of the self that is structured in specific contexts of power relations. Such embodied articulation has powerful potential for challenging the white, capitalist, patriarchal, heteronormative boundaries that structure dominant discourses of citizenship and the body politic.

I am taking the cue from Rankine’s Citizen again to reflect on a mode of critique which involves “touching” and being “touched” by art. Such a critique opens a way for rethinking and reworking the aporetic forces of logos and myth, of the textual and the visual, and of the critical and the poetic. For this critical approach the measures and rules are to be invented or re-invented in the very process of this dialogical meditation. As a performative, this critique disarticulates the economy of the unpresentability and refigures the figuration of the ‘other’ in gendered and racial terms in the textual register or in polis. In the context of this critique, the separation of aesthetics and politics emerges as a problematic one. The performativity conveyed by art is not merely aesthetic (the framing of the beautiful, as Kant’s analytic would allow and acknowledge), but profoundly ethical and political (Tzelepis, 2021). Through this interplay of critique and the arts, the aim in this collection is to problematize the epistemic, aesthetic, and cultural assumptions of both, especially regarding the ethico-politics of resistance and social transformation.

The present collection of texts seeks to prompt the question on the dialectic of art and criticism from the standpoint of social and political exigencies of our times. The goal is to address the transformative capacity of art, art criticism, and critical theory in its artful tropes and sensibilities, to actively condition or mobilize collective imaginaries and struggles contesting contemporary predicaments of power such as imperialism and war biopolitics, capitalist governmentality, and the emergence of authoritarianisms in Western democracies. This kind of joined theoretical and sensible analytics might instantiate an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary mediation that, by acting upon the limits of the present it deciphers, surfaces the very aporias of deciphering. In the spirit of aporia, then, this kind of mediation could evoke and perform the possibilities and impossibilities that mark the position of the political subject at once situated within the world and thinking otherwise and elsewhere: a position always anxious and precarious, but also always open to transgression and political hope. As the risks of aestheticization continue to contentiously engage art, art theory, and critical theory, the old but persistent question of the affirmative and/or deconstructive relationship of critique to its objects gains new currency in discussions of critical theory and art criticism today.1

Hypatia Vourloumis’s text in this collection analyzes Eirene Efstathiou’s amalgamated, durational, and fragmented painted series Memories of the present gleaned and mediated from within and across heterogeneous archives, experiences, and durations. As she explores the eventful and contingent nature of memory in Efstathiou’s art, Vourloumis meditates on the notion of crisis. The temporality of crisis, she suggests, is not permeated only by the extraordinary, the urgent, the unpredictable, but also by the banal, the recurring, the ongoing. In Foucault’s theorization, the biopolitics of epidemics and their management enabled disciplinary and surveillance measures aimed at ensuring calculable bodies and classifiable population. The exceptionality of the crisis may become a field for the naturalization of a new “normal” temporality. Pre-existing and long-standing crises within the crisis can be concealed and at the same time intensified for those exposed to the daily, normalized crises in invisible contexts of inequalities and divisions. It is not accidental that Vourloumis adds a postscript on pandemic in her text: the pandemic crisis intensified pre-existing racism towards differently situated embodied subjects to the spectre of precarity.

Could being in crisis configurate the world and public space with more political hope, however? How do we think critically in crisis? Creating art at the intersections of the reflective, the visual and the ethico-political, seems to be a response in Vourloumis’s thought:

The artworks think crisis as a narrative device and seek to bring to the fore images that speak to crisis not as an uncommon event but as norm, ongoing history, as hauntology, as mundanity and institution. Thus, the artworks presented here refrain from understanding crisis as a deviation, refuse its easy accessibility via the spectacular, and, through an archiveology, focus precisely on those objects and enactments that are considered banal and mundane as possible launching pads for alternative sites and moments of criticality and critique. (Vourloumis, this issue)

The scope of “crisis”, in this collection, includes silenced political mass violence and feminicidio in the social and political history of destruction in Colombia in the 20th and 21st century in Judith Butler’s text. Reflecting on Doris Salcedo’s art, and on how it violates the boundaries of what is publicly identifiable as a recognizable life and memorable loss, Butler is concerned with a violence that is at risk of being effaced by the overwhelming force of oblivion. These brutal losses that remain unmemorable and ungrievable produce some lives as disposable and others as viable. In so doing, they radically modify the conventional relationship between event and knowledge, language and suffering, experience and meaning, as well as politics and ethics. In contexts of exonerated and forbidden remembering and mourning, the scope of representation is limited and subjects and practices are forcibly produced in discourse through the regulation of the limits of legitimate discourse and representability. The frightening violent events exceed narrativization but also push it to its limits in Salcedo’s art objects and installations by dislocating its fundamental assumptions and technologies. How what is (not) conceivable to be happening and yet necessary to be represented is represented? In Butler’s words:

The open and relatively unanswerable question of how many died turns into the question of how to establish those deaths as mattering, and how to give material form to those deaths so that they do matter. This last is a different kind of act of accountability. “Contando muertos” names the indispensable work of establishing the record of violent death, a record of crimes against humanity, yet that counting cannot alone establish the criminality of the killing, nor can it by itself give value to those lost lives: counting is not the same as the act of mourning. After all, if we are speaking about the loss of a life, of many lives, then we are speaking about that whose value is incalculable. Even as we have to count the living and the dead, we cannot arrive at the value of the living or the dead through any counting we do. Counting can never account for the value of those lost lives. For that another mode of accountability is necessary, one that registers loss at the level of the senses, one that links the tasks of art with the labor of mourning. (Butler, this issue)

Αttempting to recall and account for a memory, especially in the context of traumatic events, constitutes a reenactment of its unrepresentability and irrecoverability (Felman and Laub, 1992). How do we give an account to the loss without contributing to its trivializing and objectification? In Butler’s perspective, the strategic use of absence in Salcedo’s work is enabling when the traumatic events eliminate their witnesses:

One reason we cannot settle on the memorial function of this set of objects is that they also exhibit the absent body in a way that does not redeem the loss by making the body present or alive again; they also conduct the very violence and destruction we are asked to register. (Butler, this issue)

Anna Papaeti’s contribution in the collection further elaborates on the question of how to represent traumatic history. The traumatic events activate a particular temporality: they interrupt the present by allowing the invocations and returns of the ghosts of the past to project into a contingent future. How do “unknown” traumatic events disrupt the monumental order and regulation of the public space? Through her analysis of the memorials on Gyaros and Vardø, she points to traumatic histories of a class war, of relentless propaganda, and of a long persecution of communism. In their own singular histories and antinomies, both memorials constitute sites of reflection of past crises but also express current political commitment to radically allow inaudible and invisible stories of terror to surface. They recall and challenge the memory of the community, occupying and memorializing its excluded and “forbidden” aspects. As Papaeti writes:

The question of how to represent traumatic history remains an open one. A dialectic with the context of the trauma revisited through materials, archival, visual, sensorial traces or other elliptic references, even through absence itself, emerges as an important perspective that allows for memorials to communicate with uninformed audiences and to retain the potency of a hit long after they are built. (Papaeti, this issue)

The narrativity of memory highlights the power relations concerning the ways in which the claims of memory, forgetting, recollection and memorability are articulated, recognized, experienced, and performed. The experience of remembering is produced in the context of an ongoing struggle over how memory is defined or what counts as a memorable memory.

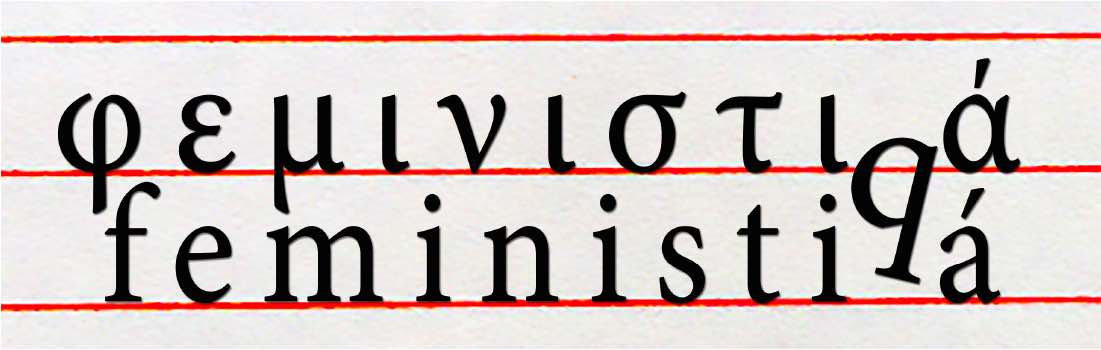

The question of how memory is a performative process of recalling and reframing activated not only in epistemic terms but also in embodied and affective terms is also explored in Meltem Ahiska’s text. How do we go beyond the referentiality of memory and towards its constitutive relation to silence, the silence of the indeterminate and the unintelligible which remains necessary for the articulation of discourse? Ahiska turns to the languages of feminism to critically rethink and remobilize the performative promises of silences. Feminism in her text stands for the abjected other of Western culture that, in resisting the proper definitions and conditions set by the economy of representation, remains irreducible, eccentric, inappropriate and unassimilable by the metaphysical closure and the ontological dichotomies of phallogocentrism. Ahiska writes:

We have to find a new language of memory for depicting this uncertainty, which is part of life; we have to find perhaps a feminine way of remembering, a fertile memory. […] Fertile memory constitutes a plural, sensuous domain of experiences and memories that are not based on binaries such as life/death, peace/war, memory/silence as abstract and governable categories. The challenging question then is not how memory counters silence, but how to make the fragments of memories fertile. (Ahiska, this issue)

The traumatic event in the texts of the collection becomes an uncertain and yet potent condition of possibility for the social and political demand for justice despite and against regimes of uneven vulnerability and enforced precarity. In this sense, the catalytic temporality of the traumatic event produces social possibilities for a contingent different future. Through this perspective, vulnerability is not grounded in nature, in spite of a long genealogy of essentialist knowledge/power regimes that maintain that there is a natural inclination of some bodies to vulnerability. Vulnerability is shaped through power relations and norms of power/knowledge that define the social. It describes the social process of constituting the subject as subjected to regulatory norms that define what counts as an intelligible and recognized subject. In this context, the concept of vulnerability refers to a social condition of producing subjects as vulnerable, disposable, and unlivable, based on gender, racial, class, ableist, and ethnic norms that set the conditions of subjectivity and survival. At the same time, vulnerability is linked to social interdependence and relationality, as it marks a limit to the liberal subject’s impenetrable self-sufficiency. How do “we”—as already permeated and constrained by social norms and regimes of precarity—relate to, and care for, one other in our mutual but unequal vulnerabilities? The way we respond to these norms, whether we are interpellated by them or desubjugated from them, is a question related to the ongoing and intractable paradoxes of subjectivation. In the context of the politics of vulnerability, “ontology itself becomes a contested field”, Judith Butler attests. In other words, at stake are the social processes through which the ontological claims that authorize the real as “order of things” are exposed and contested (Butler, 2004, p. 29).

Under historical forms of oppression, vulnerability is a ground for unequal distribution of resources and power. At the same time, it is also a field of resistant bonds of solidarity and a demand for critical and transformative modes of sociality beyond the paradigm of the self-sufficient and dominant self. This is about the possibility of subverting the normative violence that sets and distributes the conditions of survival and vulnerability (Butler, Gambetti, and Sabsay, 2016). The reflections and discussions in this collection trace the performative contestation at the heart of vulnerability and precarity. They highlight precarity as a performative resource for resistance against injurious political conditions of inequality. Isabell Lorey’s text is particularly enabling in thematizing the promising effects of precarity and becoming-precarious. In her words:

Becoming-precarious means being open for an organization in/of the present that disobeys the linear relation to the future and of which it is not yet known where it leads and what it brings, an organization in the present for which it is necessary to now take the time. (Lorey, this issue)

Let us recall Rankine’s counter-archival poetics in response to enduring white racist police violence that permeates the present. This poetics opens ways for an organization in/of the present, offering an impetus to rethink critique in arts and humanities as a call to decolonize our acutely unjust times and resist their normalized self-evidence. What becomes of the contemporary arts and humanities and their political, ethical, aesthetic, and affective lexicon when the global present is so thoroughly infused with amplified racial, gendered, and economic violence? What happens to the humanities when critically attending to the spacetime of abstract humanity and humanness as constitutively delimited by the injustices of racialization, gender, class, and ableism? What becomes of critique as an ethico-political condition and stance amidst everyday colonial capitalist injustice, nation-state securitization, and the neoliberal evisceration of the affective and material infrastructures of collective life? How might such questions become the resource and the matter for collective and relational critical thinking, imagining, and acting in the field of artistic and curatorial practices? And, perhaps most significantly for the purposes of this collection, how might our writing and reading practices put these questions into action?

Asked this way, these questions pertain to complex intersections of genres, affects, subjectivities, infrastructures, and potentialities underlying the critical force of public art. As we seek (to engage) new modes of writing, reading, imagining, thinking, performing, and sharing texts and artwork, different from formulations and formalizations of Eurocentric thought, capitalist commodification, and colonial prescriptions, we attend to the crafting of scholarship, artwork, and sociality that is foreclosed by dominant regimes of knowability, sensibility, intelligibility, and affectability. From this perspective, critically engaging with the global present requires pursing a reflection on, and positioning oneself regarding, the question “whether and how thinking through, with and after the global in the present time might allow us to decenter and displace the dominant ways of being in the world: the historical conditions in which we find ourselves and in which we are all differentially tangled up” (Athanasiou 2019; italics in the original). Kyoo Lee’s piece in this collection is part of an experimental endeavor she curated, where poets, writers, and scholars, exploring the expressive diversity of English in transition, engage the world of dynamic “Englishing” and its polyphonic futurity in various situated poetic and prose formats, and with diverse rhythms, dialects, accents, and textures (Kyoo Lee, 2020, p. 9). This is how Lee describes the “Queenzenglish,” the anticolonial practice of writing that the authors in this collective volume perform:

So, “Queenzenglish” choreographed here, a punceptual play on the

“Queen’s English,” addresses the differential mechanisms of control and

creativity, which manifest themselves so clearly and wildly in the current

social and political climate where glocal borderlessness often remains a

costly rhetoric only a few queens could afford. Queenzenglish that, in

turn, pays close attention to every queen that there is in the world of

entanglished borderiding critically questions the dominance of Anglo-

American-centered sociocultural and political norms, while creatively

engaging the site from which one speaks; Queens, for instance, the most

diverse borough of New York City, where many “Englishes” along with

hundreds of other languages are in active use. Entailed in this

homocryptophonic interplay with English is a reflexive critique of the

self-colonializing idea that knowledge and success are premised on the

mastery of the English language, a bio-politicized notion that confines

learning environments, where anglogocentrism often remains powerfully

literal. The systems that instill this ideology tend to set conformity as a

prerequisite for inclusion. Instead, we have set out to unleash the

polyphonically transformative potentials of qENG. (Lee, this issue)

In this respect, the quest(ion) why and how a complicated sense of the relationship between art and life matters for our modes of critique, dissent, and resistance is at stake. Thus, what emerges from such situated experience of mattering is a reframed, rearticulated poetics and ethics of attentiveness; in other words, a “poethics” (Ferreira da Silva 2014; Retallack, 2004). For Joan Retallack, poethics lays out occasions of inquiry, speculation, and intuition akin to “making art that models how we want to live” (2004, p. 44). The utopian connotation of poethics reveals itself in the ways poethical engagement asks how unpredictable swerves afford opportunities to radically revise habitual ways of life and art. For Denise Ferreira da Silva, a poethics of Blackness and Black feminism denotes “a whole range of possibilities for knowing, doing, and existing” (2014, p. 81). Conceptualized as such, a poethical reading of this world signals a possibility for performing knowledge, reflection, and practice (artistic, curatorial or otherwise) beyond and against the colonial and racial epistemic violence inherent to institutions, protocols, and formulations regulating contemporary art political economies and discourses. This performative possibility implies constantly challenging the power-knowledge structures of criticism authorized by the Western matrix of universal reason—in all its constitutive and persistent capitalist and colonial underpinnings.

It has been, then, my wager in this introductory text to argue for a critical that involves, presupposes, and requires the poethical; a critical that allows itself to be constantly rewritten by the poethical. Put differently, I would like to point beyond established forms and oppositions of critical and poethical, ethics and aesthetics, poetics and politics. This criss-crossing of multifold boundaries might allow us to trace—and learn from—potentially transformative paths against the grain of the cultural logics mandated by white supremacy, neoliberal governmentality, and cis-heteronormativity in our present times. Such troubling and overcoming of boundaries is registered in the making of art which articulates modes of resistance to interlocking power limitations, such as precarization, commodification, disenfranchisement, censorship, undermined labor rights, as well as racial and gender privileges and inequalities, in ways that question the grand-narrative (i.e., exceptional, extraordinary) conceptions of contestation, thus implying a reflective transformation of habitual understandings of critical agency. In all, through an epistemological and political commitment to the nuanced intertwining of discourse, art and the temporality of existence, a notion of critique of power-knowledge constellations may be articulated and refigure political possibility against the seeming givenness of the present. What is at stake, then, is a reconfiguration of public presence in the realm of the relatedness of art to the world. In her Documenta 14 performance “Presence,” which took place in an immigrants’ neighborhood in Athens, the artist Regina José Galindo wears the dress of a murdered woman from Guatemala City. The dress was lent by her family, which keeps the memory of their loved-one alive through this garment. The haunting co-implication of present and presence amounts here to spectralized/spectralizing and specularized/specularizing difference not subsumed from normative closure, completion, and commensuration.

Shifting available and dominant conceptions and boundaries of both art and critique, this collection seeks to reflect on the performativity of art and critical thought as they become critically positioned in and responsive to the structural ‘crises’ of the present world. In chronicling the contested possibility of arts and acts of critique during increasingly precarious times, when the public spaces for performing critical practices are at stake, the pieces of this collection provide ways of navigating, recounting, and countering the normalized configurations of the present, amidst and despite collective exhaustion. Through different genres, and against the backdrop of a racial capitalist art industry, they point to critical forms and infrastructures of knowledge, desire, care, and poethics; they call attention to critical modes of public as well as possibilities for a critical public attentiveness in the world.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the authors of this collection for all our ongoing conversations. My warmest thanks also to friends with whom we shared ideas, concerns, and visions in the context of the panel we co-organized with Athena Athanasiou for the international conference New Narratives: Thinking Economics differently 2: A Summit on Art, Theory and Civil Society, Stuttgart, April 2018 as well as the international symposium we co-organized with Natalia Brizuela for the International Consortium of Critical Theory, New Mexico, September 2018. I am indebted to Alkisti Efthymiou and Aliki Theodosiou for their inspiring and generous help with this collection.

Endnotes

1 Athena Athanasiou insightfully asks whether and how the aesthetic can serve as a resource for making sense of the question of possibility and for developing a conception of critical subjectivity, in treating critique as an experience of the im-possible, and yet as a transformative force for shifting the conditions of possibility for knowledge production (Athanasiou, 2020).

REFERENCES

Athanasiou, A. (2020). At odds with the temporalities of the im-possible; or, what critical theory can (still) do. Critical Times, 3(2), 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1215/26410478-8517735

Athanasiou, A., & Sheikh, S. (2019). Formations of political-aesthetic criticality: Decolonizing the global in times of humanitarian viewership – Athena Athanasiou in conversation with Simon Sheikh. In P. O’Neill, S. Sheikh, L. Steeds, and M. Wilson (Eds.), Curating after the Global: Roadmaps for the Present (pp. 77–100). MIT Press.

Berlant, L. (2014, October 1). Claudia Rankine by Lauren Berlant. BOMB Magazine. Retrieved August 29, 2020, from http://bombmagazine.org/articles/claudia-rankine/.

Butler, J. (1997). The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford University Press.

Butler, J. (2001, May). What is Critique? An Essay on Foucault’s Virtue. transversal. Retrieved August 29, 2020, from https://transversal.at/transversal/0806/butler/en.

Butler, J. (2004). Undoing Gender. Routledge.

Butler, J., & Athanasiou, A. (2013). Dispossession: The Performative in the Political. Polity Press.

Butler J., Gambetti Z., & Sabsay, L. (Eds.). (2006). Rethinking Vulnerability: Towards a Feminist Theory of Resistance and Agency. Duke University Press.

Da Silva, D. F. (2014). Toward a Black Feminist Poethics: The Quest(ion) of Blackness Toward the End of the World. The Black Scholar, 44(2), 81–97.

Dimitrakaki, A., & Perry, L. (Eds.). (2013). Politics in a Glass Case: Feminism, exhibition cultures and curatorial transgressions. Liverpool University Press.

Felman, S., & Laub, D. (1992). Testimony: Crises of witnessing in literature and theory. Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1997). What is Revolution? (L. Hochroth, Trans.). In S. Lotringer (Ed.), The Politics of Truth (pp. 83–95). Semiotext(e).

Foucault, M. (2001). Truth and power. In J. Faubion (Ed.), Power: The Essential Works of Foucault 1954–1984, Vol. 3 (pp. 111–133). The New Press.

Krasny, E., & Perry, L. (Eds.). (2022). Curating as Feminist Organizing, Routledge.

Krasny, E., & Perry, L. (Eds.). (2023). Curating with care. Routledge.

Lee, K. (Ed.). (2020). Queenzenglish.mp3: poetry | philosophy | performativity. Roof Books.

Rankine, C. (2014). Citizen: An American Lyric. Penguin.

Retallack, J. (2004). The Poethical Wager. University of California Press.

Tzelepis, E. (2021). Art’s political criticality: At the thresholds of difference and eventuality. Synthesis: an Anglophone Journal of Comparative Literary Studies, 0(13), 181–206. https://doi.org/10.12681/syn.27570