De-commodifying political memory: Fertile memories beyond the walls of silence

Meltem Ahıska

The impulse to create begins –often terribly and

fearfully– in a tunnel of silence.

Adrienne Rich (2002, p. 78)

Memory is often contrasted to silence. Memory is active in resisting repression and defending the forces of life, while silence –a product of silencing– submits to power and domination. This essay aims to problematize the binary of memory/silence by suggesting that we consider silence not simply as void or absence but as a worldly texture carved out of marginalized experiences and shattered dreams, of forlorn lives and deaths, perhaps like a “tunnel of silence” that we can work through. The traces and fragments of memory continue to exist in silence albeit dispersed in time and space. The unmaking of the binary of memory/silence is significant in my view for de-commodifying political memory. There is a danger that political memory becomes dependent on the interconnected logics of market and law and loses its vitality for imagining collective well-being and justice. This is also how political memory succumbs to decontextualized violence that flattens the diverse temporalities of remembering and dispossesses the marginalized segments of society of the agency to remember. Thus, the essay offers another conception of memory: “fertile memory” (Al-Qattan, 2007) that resists the hegemonic discourse of memory under the present circumstances. As I will discuss later, fertile memory resonates with what Foucault has called “counter-memory” (1977). The politics of fertile memory engages with potentiality, imagination and futurity, and in doing so focuses on the silenced margins of history and memory.

Memory, law, and silencing

The events that have motivated me to write on this subject have now been almost totally criminalized and silenced: namely, the war in the Kurdish regions of Turkey that was rekindled in 2015, after a brief lapse with the so-called peace process of negotiations between the Kurdish political movement and the Turkish state. This conflict has led to devastating transformations in many places including Sur, a historical district of Diyarbakır. I am among the “Academics for Peace” in Turkey, who have been criminalized in different ways for having signed a petition released in 2016 against the war and the severe human rights violations in the Kurdish provinces, demanding that the peace process that had begun a few years earlier be restarted.1 Many academics lost their jobs in the universities immediately after signing the petition, many were threatened, many were subject to travel bans.2 Four academics who read the public statement of the Academics for Peace against the targeting and attacks in a press conference in March 2016, were arrested and put into prison. The individual court cases of the Academics for Peace began almost two years after the publication of the petition. The delayed timing of the law points to the need to forge an official memory to publicly remind once again that a defiant act against the state is punishable. The law has thus imposed its own time to summon the individual to become a hostage in the violent economy of law as well as war. In the court cases starting at the end of 2017, the academics have been accused for siding with terrorists. The indictment claimed that these academics have taken orders from a terrorist Kurdish organization. The Academics for Peace, on the other hand, have defended themselves in the courts, raising various issues and arguments for peace and against the war.

Although the defense statements of the academics in the courts constitute an alternative archiving of war and suffering and, thus, provide a significant testimony to what has happened, political memory is nevertheless forced to go through a legal framework and gets fixed in a particular way. Emanuela Fronza in her discussion of law and memory argues that in many cases “the criminal trial intervenes to ‘establish’ events of the past and to impose an official ‘truth’” (2018, p. 113). Historical reconstruction becomes one of the primary functions of the criminal trials. “However, historical reconstruction and judicial reconstruction have different methods, logics and objectives” (Fronza, 2018, p. 113). Historical reconstruction is complex and fluid, whereas criminal law solidifies events and withdraws them from that “fluid dimension of memory and historical reconstruction” (Fronza, 2018, p. 116). The judgment of criminal law overshadows the political statements in the court rendering them ineffective for remembering the assessed “events” in their complexity and historicity. As Giorgio Agamben argues, judicial judgment is self-referential. “If the essence of the law –of every law– is the trial, if all right (and morality that is contaminated by it) is only tribunal right, then execution and transgression, innocence and guilt, obedience and disobedience all become indistinct and lose their importance” (1999, p. 19).

One of the burning issues silenced during the judicial reconstruction of “events” in the trials of Academics for Peace in Turkey is the vital meaning of peace. Almost all the statements for the defense have raised the issue of peace through various angles, but since peace is taken as a charged word associated with terror by the courts, the image of peace eventually gets boiled down to a one-dimensional term operative in defense as opposed to war. The judgment as punishment fixes and devitalizes the meaning of peace,3 “which does not permit of an external perspective that would break the epistemic framework of war itself.”4 In other words, peace is either associated with terror, or contrasted to war. Peace is stripped of diverse experiences, for which no language and space exist in the courtroom. The law monitors time to create a flat entity; different temporalities, events, and plural perceptions preceding, surrounding, and following the referred events are bracketed off.

I would argue that the purported antinomy of war and peace reinforced by the logic of law has a captivating spell on the way we think of memory today. War and peace are highly interconnected both practically and symbolically. It is as if we need to evoke war in order to imagine peace as the end of war. Starting from the Second World War to the current “wars on terror,” wars have been presented as justified ways of ending wars. This leaves us with a dire image of peace. Is there an image of peace that could be associated with a particular non-war experience? What role does memory play in activating this image? Can we imagine an alternative way of relating to the world in which images of peace would not be exchanged for those of war? How does memory resist commodification in this process?

The status of experience, and the memory of the senses in and through the space of experiences are pivotal for this discussion. Nadia Seremetakis argues that senses represent inner states but that they are also located in a social-material field outside of the body (1994, p. 5). As she states,

Mnemonic processes are intertwined with the sensory order in such a manner as to render each perception a re-perception. Re-perception is the creation of meaning through the interplay, witnessing, and cross-metaphorization of co-implicated sensory spheres. Memory cannot be confined to a purely mentalist or subjective sphere. It is a culturally mediated material practice that is activated by embodied acts and semantically dense objects. (Seremetakis, 1994, p. 9)

The erasure of sensory memory renders the senses imperceptible. This is also the erasure of the meaning of experience. If, as Walter Benjamin has argued, war deprives us of experience –“For never has experience been contradicted more thoroughly than strategic experience by tactical warfare, economic experience by inflation, bodily experience by mechanical warfare, moral experience by those in power” (2007, p. 84)–, peace also has become a hollow concept with no sense perception and memory, other than being the opposite of war. War becomes the non-sensory repository of peace, so much so that even the mongers of war can utilize the image of peace today. For example, the military operation of Turkey in Afrin was called “the olive branch operation,” olive branch being the most popular, perhaps one of the few remaining symbols of peace in our region. It has been appropriated to stand and persevere as a symbol of war.

Allen Feldman in his essay on cultural anesthesia (1994) gives a highly alarming example of the de-sensualization, perhaps we could also say the commodification of the memories of war and peace, by citing the words of a resident of besieged Sarajevo in the early 1990s:

We lost any sense of seasons of the year, and we lost any sense of the future. I don’t know when the spring was finished, and I don’t know when the summer started. There are only two seasons now. There is a war season, and somewhere in the world there is a peace season. (Feldman, 1994, p. 404)

This statement from the midst of war is striking! The seasons that we perceive through our senses are numbed and replaced by the so-called seasons of war and peace that do not provide any sensory stimuli, but are only exchanged in a vicious cycle. In Turkey, too, the war season has been going on for too long. And “peace” is a very fragile yet dangerous word. Those in power who portray war as beneficial for the nation, and those who oppose war and demand peace are at a constant war on all fronts of the society, including the theater of law. But the biggest problem is that the image of war reigns in both, leaving us with silenced and contested memories of what peace could have meant for our lives.

Memory, economy, and violence

The commodification of memory entails the homogenization of diverse temporalities and experiences; it is a process of abstraction. Marx argues that abstract undifferentiated human labor provides the key to understanding the enigma of the commodity, which seems to be a real object but has an exchange value surpassing the singularity of the object. The commodity is both perceptible because it is an object and imperceptible because it contains embodied abstract human labor. The abstract labor that produces exchange value gives a mysterious character to the commodity, but it is the outcome of a real process: labor power is homogenized, quantified, massified, and exploited at the site of capitalist production. The process is indeed a violent one, crushing individual bodies, histories, and dreams. The violence is disguised under the general title of economic production. There is a particular silencing of the collectivized sensuous human activity here that resembles the silencing of memories. When memories are also molded into abstract concepts deprived of any sensory connotations, they can be exchanged as in the case of peace and war. They hide the violence of abstraction. Silencing of memories is a product of this abstract violence, which is de-contextualized and de-materialized so that violence is no longer something that demands historical perception and understanding. Feldman talks about “commodification of perception” in modern capitalist society referring to “new media technologies, the manufacture and consumption of reproducible mass articles and experiences, advertising, new leisure practices, the acceleration of time, and the implosions of urban space,” all of which involve “the remolding of everyday sensory orientations” (1994, p. 406). “Manifold perceptual dispositions” are repressed, which in turn dematerializes violence: “the embodied character of violence is evaded, ignored, or rewritten for collective reception” (Feldman, 1994, p. 406). The memory of violence becomes a commodity.

On January 4, 2016, a few days before the petition of Academics for Peace was publicized (January 11, 2016), an article on the great urban transformation planned for Sur, a historic district at the heart of Diyarbakır, appeared in a pro-government newspaper Sabah. Sur had just undergone devastating material and human destruction during the military operations. The article published images of destruction and devastation with captions written in a dry language of finance promising a “paradise.” For the sake of illustrating the extent of the saturation of financial language into the images of devastation and suffering, I quote a large segment from the captions that accompany the images of war in the newspaper article:

A new transformation process starts in Sur. Among the nine thousand buildings, the historical ones will be put under protection. With a four-billion lira investment Sur will be paradise again. Those citizens who have been victimized because of terror will be supported to have good prices for the new houses […] The transformation will cover a land over a million square meters. The project run through the coordination of the Ministry of Environment and Urbanism, the Ministry of Interior, and the Public Housing Administration has the principle of less housing and more commerce […] The buildings will not be higher than four floors […] No building will be higher than the city walls. The old houses will be expropriated according to the market prices […] But the market prices will be determined according to the values of the houses before the unrest, namely the armed struggle in the region […] Our citizens will be protected from financial loss […] First there will be a risk and damage assessment. The wounds of the citizens will be redressed, and the buildings will be inspected to see whether they are habitable. After the assessment, buildings deemed dangerous will be demolished […] The urban transformation project makes use of the 1930 photographs of Sur taken by the famous art historian Albert Gabriel.5

At the end of the article, a high-level financial executive is cited, who seems to be a more trusted authority than any historian: “Sur is one of the most important centers in Turkey with its history and natural habitat. Sur will become one of the paradises of Turkey.” Here we see how seemingly different concerns such as the protection of cultural heritage, the paternalist attitude of the state towards its subjects, and the sheer financial interests in this newly emerging market combine. The discourse not only financializes but also aestheticizes the violent destruction, turning the site and particularly its history and nature into a commodity. In the end, the place becomes easily exchangeable with any other place in the world. As the then Prime Minister of Turkey Ahmet Davutoğlu announced, “Sur will become like Toledo,”6 an attractive tourist site in Spain.

This is a perfect example of what Allen Feldman has called the “actuarial logic of politics” that posits “actuarial terms such as risk, loss, indemnification, reparation, restoration, value, equivalence, and collateral damage.” He argues that an “economic logic underlies our cultural understanding of the political act of terror –an economy of violence that speaks of, measures, and compares acts of violence and damage in actuarial terms of loss, magnitude, and compensation” (2003, p. 70). The actuarial logic also informs the structures of memory and forgetting. It erects a vicious cycle of remembering and forgetting in a rubbed-down, smoothened, yet haunted, space and time, devoid of experience. As a result, I focus on the question of the differential visibility, or shall I say audibility, of silences. While obsessed with the duty of memory to counter the most apparent silences forged by dematerialized violence, what kind of other memories that bear historical possibilities for futurity are marginalized? Most opponents of war hold on to the devastating memories of war, but they are condensed, abstracted, hence involuntarily commodified in a way to make other –what I would call the life-giving, multiple sensory memories or fertile memories within the same site– unthinkable.

The unthinkable and fertile memory

Silence, like memory, has its own fragmented texture. In Silencing the Past (1995) Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues that “silences enter the process of historical production at four crucial moments: the moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance)” (1995, p. 26). According to Trouillot, all silences are not equal and they cannot be addressed, or redressed, in the same manner. Diverse types of silences crisscross or accumulate over time to produce a unique mixture. Here I would like to focus for the sake of my arguments on the last moment of silencing: that of making history. Trouillot’s discussion of Bourdieu’s concept of the “unthinkable” as a way of silencing is significant in this respect. Unthinkable is that “which one cannot conceive within the range of possible alternatives, that which perverts all answers because it defies the terms under which the questions were phrased” (Trouillot, 1995, p. 82). For Trouillot, the Haitian Revolution was unthinkable because “it challenged the very framework within which proponents and opponents had examined race, colonialism, and slavery in the Americas” (Trouillot, 1995, p. 83).

Sur, the historical district of Diyarbakır, is currently associated in oppositional discourse with the military operations of the state against the Kurdish political movement. As I have discussed above, these operations have been lethal and harmful for a large group of civilians. The legal framework contributes to another historical reconstruction by solidifying the events as a result of terrorist activities, thus criminalizing the defenders of peace as siding with the terrorists. The ongoing urban transformation, on the other hand, attempts to erase all memories of the war and human rights violations in order to set up a blank space for a new market of housing and tourism equated with “paradise.” However, what remains unthinkable in all these accounts are the multiple and layered memories of life and silencing in the district of Sur.

Sur is a particularly significant area where there is a palimpsest of silencing enacted by violent interruptions at different times in its history. Sur is an ancient district in Diyarbakır, surrounded by city walls. Actually, Sur means city walls. It is also known as the “Infidel Quarter,” because of the Armenians, Syriacs, and Keldanis who lived there for centuries. Mıgırdiç Margosyan’s memoir entitled Gavur Mahallesi (Infidel Quarter) (2017) vividly narrates the everyday life stories of the remaining Diyarbakır Armenians, who survived the Armenian genocide of 1915 and have continued living in the Sur district. Many had to leave Sur in the 1990s when the war between the state and the Kurdish forces intensified. The translator’s foreword to the recent publication of the book in English is striking for showing the entanglements of violence and silencing:

Who would have thought that in 2016, the Sur district of Diyarbakır would endure new calamity and destruction? In a protracted struggle between Kurds fighting for autonomy and the state, much of Margosyan’s Diyarbakır has been laid to waste by modern warfare, the use of heavy weapons, and the political designs of the state to bring the area under its control. Many have argued that this has been a political war to silence Kurds through death and intimidation, the sequestration of properties, and the erasure of memory. The state is already talking about the gentrification of Diyarbakır and the creation of a more compliant Turkish city. Margosyan’s world has now been dealt another blow and probably lost forever. (2017, pp. ix-x, emphasis mine)

It is tragic that Margosyan’s world could have been lost forever, but his book also captures a world that was lost in an even more remote past. Reading the memoir, one gets the feeling of another, unthinkable kind of loss: the loss that does not only pertain to buildings of historical importance, such as the historical churches, but also to forms and ways of cohabitation of Armenians, Syriacs, Keldanis, Kurds and Turks. This way of life is unthinkable because it fits neither the antinomy of war and peace, nor the discourses of nationalism and terrorism. Sur has been primarily a district of artisans where the interaction between all kinds of people, animals, things, religious practices, and languages produced the rich sensory environment of everyday life. However, I refer to Margosyan’s memoirs of Sur not to claim that once there was an idyllic and peaceful life. Actually, the stories illustrate many instances of power relations between the rich and the poor, between the abled and the disabled, and particularly between women and men –for example, people did not regard girls as a desired child and continued making babies until a boy was born. However, these experiences of inequality had a dimension of worldliness within which people performed to make the place and the life within the place, sometimes in harmony, sometimes fighting and struggling with each other and the world. Embodied violence did not only lead to destruction at times, but also to unexpected moves and encounters that generated new modes of life. Memories belonged to the place and were processed through senses in differential ways of belonging, depending on earthly and bodily dispositions such as wealth, age, skills, ability and sexuality.

I remember a folk song from the Eastern parts of Turkey that enacts such a place of memory:

“Smoke has covered those serene mountains

Yet more bad news from abroad?

Who has cried at these places at dawn?

There are teardrops over the grass”7

Suffering and pain are made visible here without pointing to a definite individual subject. Memory is described as belonging to the place. In these narratives, including the folk songs, which bring along some faded memory fragments from the past into the present, we see that memories are embodied and emplaced, with a potential to nourish a range of creative acts, songwriting as well as political resistance. This is exactly what is silenced in memory as political commodity.

The annihilation of place and belonging to place through violence introduces us to the most persistent political questions in the present time, informed by the nationalization/capitalization of time and space. The re-codification of a heterogeneous territory under national terms and the consequent leveling off of different and entangled temporalities have targeted subaltern groups by sequestrating their memories and the power of their memories to make not only the place, but also the past. Obviously, this is not merely a symbolic process, but it is enacted through economic, political and social forms of power, which involve both literal destruction and displacement, and the education of desire and construction as destruction8 in the name of “progress.”

The loss of sensory memories today then is also the loss of the world in which they have been sensed and made. Within the logic of war, the place becomes not a site, but a medium of warfare: “a flexible, almost liquid matter that is forever contingent and in flux” (Weizman, 2007, p. 186). There remains only “the wretched” after the catastrophe: both in the registers of the state and in the humanitarian discourses on war and peace. Kristin Ross points to a new regime of representation that shapes the “humanitarian victim,” the “wretched of the earth” that Fanon had written about, who now with the disappearance of the lived dimension of the earth, “had become, quite simply, the wretched –stripped, that is, of any political subjectivity or universalizing possibility and reduced to a figure of pure alterity: be it victim or barbarian” (Ross, 2002, p. 12). While Fanon’s “wretched of the earth” was the name for an emergent political agency, now it has been substantively reinvented: “its agency has disappeared, leaving only the misery of a collective victim of famine, flood, or authoritarian state apparatuses” (Ross, 2002, p. 157). The “wretched” is a product of de-contextualized violence.

Yet I contend that our capacity to be affected by others in this world still provides a significant potential for memory that remains dormant due to the subject positions created by de-contextualized violence. We need to critically reflect on this potential in order to activate sensory memories and listen to silences through different encounters. Neither memory nor silence is a clean-cut concept. Silencing suppresses memories, but as the musician of silences John Cage has said, “there is no such thing as silence. Something is always happening that makes a sound.” Walls of silence are built so that the sounds within silence are not heard. There is no pure and abstract memory either. Actually, there is no closure to memory narratives; in that sense, there is an impossibility of memory that can be unproblematically associated with a particular identity or place. However, it is inevitable that we encounter the erupting fragments of memory; hence there is also the inevitability of memory. Memory has a gravitational force; memory attracts us. We have to find a new language of memory for depicting this uncertainty, which is part of life; we have to find perhaps a feminine way of remembering, a fertile memory as the Palestinian filmmaker Omar Al-Qattan puts it.9

Qualifying a potential new language of memory with terms such as fertile and feminine, I do not intend to abide by the meanings given in existing gender ideologies. Quite the opposite. Mine is an attempt for the desorption of the violated and silenced perceptions/memories in modern patriarchal regimes. I have suggested earlier (2018) that we can approach “the feminine through a negative dialectic, by extracting from history the possibility (and embodying that very possibility) of what has been suppressed, attacked, and violated as feminine; by coming to terms with the persistent historical structuration that has made the feminine not only the other, but also extremely vulnerable in economic, political and cultural life.”10 For this we need to go beyond the hegemonic subject of violence and memory –imagined after a “masculine response to catastrophe” (Al-Qattan, 2007, p. 199)– and caught between the burden of the past and the need to forget and start anew. Fertile memory constitutes a plural, sensuous domain of experiences and memories that are not based on binaries such as life/death, peace/war, memory/silence as abstract and governable categories. The challenging question then is not how memory counters silence, but how to make the fragments of memories fertile.

Omar Al-Qattan argues that for making our memories fertile, we can reinvest “our anger, bitterness and nostalgia with a new defiance and a new vision for the future” (2007, p. 201). Memories coalesce at unexpected moments and reveal themselves in a new light. “We need to think of memory no longer simply as assertion and testimony, but as the point of a new departure” (Al-Qattan, 2007, p. 204). Fertile memory is a feminine way of remembering the textures of silence, the shaded colors of life that nourish a sense of both defiance and hope in the present. The site of fertile memory is the silenced everyday life, mostly associated with women, and that is not usually elevated to the level of historical construction both in legal and financial terms.

Fertile memory is related in some aspects to what Michel Foucault has termed as “counter-memory” (1977). Foucault does not elaborate his discussion on the concept; instead, the term is briefly mentioned within a context of what makes “historical sense” different from “monumental history” in Nietzsche’s terms. Foucault says:

The historical sense gives rise to three uses that oppose and correspond to the three Platonic modalities of history. The first is parodic, directed against reality, and opposes the theme of history as reminiscence or recognition; the second is dissociative, directed against identity, and opposes history as continuity or representative of a tradition; the third is sacrificial, directed against truth and opposes history as knowledge. They imply a use of history that severs its connection to memory, its metaphysical and anthropological model, and constructs a counter-memory—a transformation of history into a totally different form of time. (1977, p. 160)

When thought together with his concept of “counter-history” that aims to look at the other side of the social body left in shadow or in darkness (Foucault, 2004, p. 70), we can understand counter-memory as a way of disrupting hegemonic continuities and traditions of memory. In other words, it is a way of approaching the gaps and voids in narratives that are constituted through silencing. I would argue that fertile memory provides the paths of counter-memory because it attends to plural and multiple bodies, senses, and places and the way experiences are always entangled in history, instead of commodified memories bred by de-contextualized violence. Fertile memory reveals the texture of silencing, which is always dispersed, yet particular and concrete. “Contrapuntal sensory histories can be recovered from the scattered wreckage of the inadmissible: lost biographies, memories, words, pains, glances, and faces that cohere into a vast secret museum of historical and sensory absence”, says Feldman (1994, p. 415). We can visit the secret museum of historical and sensory absence to imagine and re-make the world. Not only as a historical reconstruction to know what has been, but also to imagine what could have been in a tunnel of silence that has a creative futurity.

Epilogue

…I remember a very different Sur, not as a site of destruction, but as a site of women making things happen. Diyarbakır was declared a women’s city for three days in March 2010 by the municipality then run by the Kurdish party. I was there to participate in a panel. The meeting room was packed with women. Some were militants fighting for the political cause. Some had taken administrative roles in the municipality. Some came from far away, from the surrounding villages; there was still mud on their shoes. They were all wholeheartedly participating in the conversations, asking questions, raising ideas, and debating ideas […] There was such a vibe in the whole city […] Several activities were going on: lectures, panels, dance and theater performances, collective dancing in the parks, demonstrations in the streets […] Women took us –the visitors– proudly to collective laundry rooms, introduced us to the services designed particularly for women. We walked along the streets of Sur and looked at the sites of ancient, wounded, yet still alive history. I thought that all this happened, it happened and could happen! Imagining another life, another place was possible despite the grave political pressures. I thought about the right to be hopeful, which is foreclosed under current conditions. If I have one image of peace now, it is the image of women coming together and doing things, while gossiping, complaining, shouting, talking about their dreams and pains in languages in which they feel at home.

Endnotes

1 One thousand two hundred and twenty-eight academics signed a petition, which was entitled “We will not be a party to this crime”, condemning the severe human rights violations under the curfews declared during military operations that started in mid-2015 in several cities in the south-eastern regions of Turkey. The petition was publicized on January 11, 2016. Later, with the addition of new names, the number of supporters reached 2,215. The petition was presented to the Turkish Parliament on January 21, 2016. There was also a list of a group of national and international supporters attached to the file. The academics who have been targeted and criminalized as a result of this petition came to be referred to as Academics for Peace.

2 For a critical discussion of what happened before and during the trials of Academics for Peace see Judith Butler and Başak Ertür, “Trials Begin in Turkey for Academics for Peace”, Critical Legal Thinking, Law and the Political, December 11, 2017. https://criticallegalthinking.com/2017/12/11/trials-begin-turkey-academics-peace/ (last accessed May 18, 2022).

3 As of January 2019, the number of Academics for Peace tried in the courts was 568. In 81 of these, the trial came to a conclusion: 69 academics were sentenced to 15 months of prison, and the punishment was suspended. Yet, there were others, who received from 18 to 30 months of prison with no suspension. The varying punishments were based on the same indictment prepared by the public prosecutor for the Academics for Peace. See also Tören and Kutun (2018). In July 2019 assessing the appeal of some academics, the Constitutional Court decided that the academics’ freedom of expression has been violated, after which came the acquittals in the trials and re-opened trials. Although more than 500 academics were acquitted in this process many academics could not go back to their jobs in the universities in the end. Furthermore, many academics were removed from their university positions by decrees having the force of law; they were left with no academic job opportunities in Turkey, and those who had their passports revoked could not go abroad. Those who felt obliged to leave the country still live in exile. Overall, a substantial number of Academics for Peace were very badly affected by the interconnected operations of law and extralegality, and were sentenced to civil death. Tansu Pişkin, “Barış Akademisyenlerinin Kısa Tarihi: Hedef Gösterilme, İhraç, Yargılama” Expressioninterrupted, February 6, 2020. https://expressioninterrupted.com/tr/baris-akademisyenlerinin-kisa-tarihi-hedef-gosterilme-ihrac-yargilama/ (last accessed May 18, 2022).

4 Judith Butler and Başak Ertür, “Trials Begin in Turkey for Academics for Peace,” Critical Legal Thinking, Law and the Political, December 11, 2017. https://criticallegalthinking.com/2017/12/11/trials-begin-turkey-academics-peace/ (last accessed May 18, 2022).

5 “Sur’da büyük dönüşüm!”, Sabah, January 4, 2016. https://www.sabah.com.tr/galeri/turkiye/surda-buyuk-donusum (last accessed January 15, 2019).

6 “Davutoğlu: ‘Sur, Toledo gibi olacak”, Milliyet, February 1, 2016. http://www.milliyet.com.tr/davutoglu-sur-toledo-gibi-olacak-ankara-yerelhaber-1191664/ (last accessed January 15, 2019).

7 Şu yüce dağları duman kaplamış/Yine mi gurbetten kara haber var?/Seher vakti bu yerlerde kimler ağlamış?/Çimenler üstünde gözyaşları var.

8 See Şemsa Özar (2017) for the dynamics of construction and destruction in the Sur district.

9 Omar Al-Qattan, in his beautifully written piece on the “Secret Visitations of Memory,” narrates two different experiences of memory. He has accompanied both his father and his mother at different times in their journeys back to their hometowns, consecutively to Jaffa and Tulkarem in Palestine after years of exile. He says, “the two separate experiences that I shared with my mother and father revealed two contrasting ways of remembering” (2007, p. 199). His mother’s was a “feminine recollection […] more redolent with life, more contemporary” than his father’s experience, which resembled a “masculine response to catastrophe” associated with “weighty things that we often carry around with a sense of guilt, or shame or regret” (2007, p. 204). “And these two types of remembering permeate the many varied ways in which Palestine has been sung, eulogized, missed, symbolized –in other words, to use a fashionable term, the ways it has been ‘represented’” (2007, p. 199).

10 See Ahıska (2018) on feminine politics for the potential and critical meanings of “femininity.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Agamben, G. (1999). Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive (trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen). Zone Books.

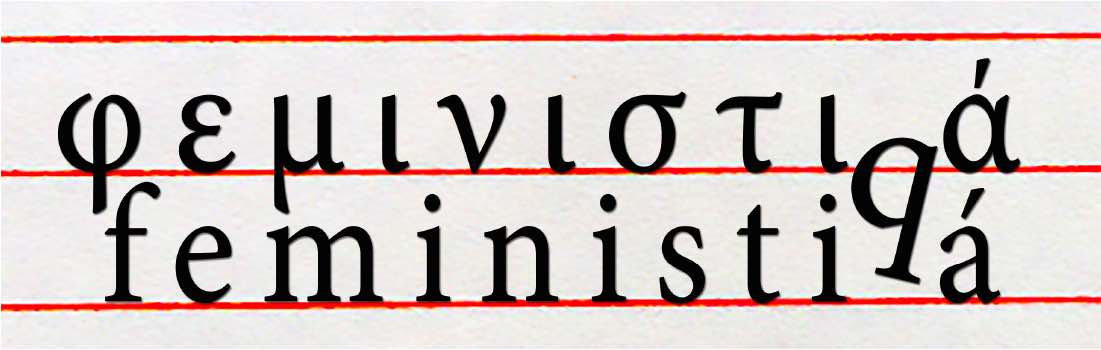

Ahıska, M. (2018). The power-drive and the time of feminine politics. Feministiqá, 1. http://feministiqa.net/the-power-drive-and-the-time-of-feminine-politics/

Al-Qattan, O. (2007). The Secret Visitations of Memory. In A. H. Sa’di & L. Abu-Lughod (eds.), Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory. Columbia University Press.

Benjamin, W. (2007). The Storyteller. In H. Arendt (ed. and intro.), L. Wieseltier (preface), Illuminations. Schocken Books.

Butler, J. & Ertür, B. (2017). Trials Begin in Turkey for Academics for Peace. Critical Legal Thinking, Law and the Political, December 11. https://criticallegalthinking.com/2017/12/11/trials-begin-turkey-academics-peace/

Feldman, A. (1994). On Cultural Anesthesia: From Desert Storm to Rodney King. American Ethnologist, 21(2), 404-418.

—– (2003). Political Terror and the Technologies of Memory: Excuse, Sacrifice, Commodification, and Actuarial Moralities. Radical History Review, 85, 58-73.

Foucault, M. (1977). Nietzsche, Genealogy, and History. In D. F. Bouchard(ed.), Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Cornell University Press.

—– (2004). Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France 1981-1982 (trans. Graham Burchell). Picador.

Fronza, E. (2018) Memory and Punishment: Historical Denialism, Free Speech and the Limits of Criminal Law. Asser Press.

Margosyan, M. (2017). Gavur Mahallesi (Infidel Quarter) (trans. Matthew Chovanec). Aras Yayıncılık.

Özar, Ş. (2017). Diyarbakır-Suriçi: İmha ve inşa, direniş ve dayanışma. Express, 154, 4-5.

Pişkin, T. (February 6, 2020). Barış Akademisyenlerinin Kısa Tarihi: Hedef Gösterilme, İhraç, Yargılama. Expressioninterrupted. https://expressioninterrupted.com/tr/baris-akademisyenlerinin-kisa-tarihi-hedef-gosterilme-ihrac-yargilama/

Rich, A. (2007). Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations. W.W.Norton and Company.

Ross, K. (2002). May ’68 and Its Afterlives. The University of Chicago Press.

Seremetakis, N. (1994). The Memory of the Senses. In N. Seremetakis (ed.), The Senses Still: Perception and Memory as Material Culture in Modernity. The University of Chicago Press.

Tören, T. & Kutun, M. (2018). ‘Peace Academics’ from Turkey: Solidarity Until Peace Comes. Global Labour Journal, 9(1), 103-112.

Trouillot, M.-R. (1995). Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press.

Weizman, E. (2007). Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. Verso.