Public discussion of the Black Feminism Lab

United African Women Organization, Greece

Esra D.:

Before I speak I want to open up the topic about an issue that we were discussing in the workshop. Greece has amazed me with the process of not legalizing but instead of trying to illegalize you. So a lot of times for example when people were asking my status I would say I am neither “legal” nor “illegal”, I am “semilegal”. Which is like, I had in my eight years of stay in Greece more times of blue paper than a resident permit which actually seems like a legal paper that gives you the right to make certain things, but the borders are closed. And it goes the same every time that you make the renewal.

And also, that fact, for example, that happened to me in the last one and half years, like last year I stayed two years illegally in the sense that I could not even pay a bill, or take a paper from KEP (Citizen’s Service Center) because I had to renew my category [type of residence permit]. And I made an application two months ago which they gave me after four months, which means there is these two months [period] where you wait for your interview in which you stay in a totally illegal [status] –and they say “okay the police will not do to you anything. They will understand that your are in a waiting process”. But you cannot do anything official.

So that struggle is what we were talking about, that is, a really heavy burden on us. And like you cannot rent a house, you cannot even apply for a job at that moment. You cannot sign a paper.

And then, when you renew it they always tell you to come two days before [it is ready]. And last week I went and there was technical problem so I had to wait. And this kind of things are the things that are not really written or talked [about]. And there is this huge problem of semi-legalizing, that we are constantly facing in our daily lives.

One of the topics, that we were discussing in the workshop, I want to talk about in this discussion is borders. Maybe you heard about the femicide of three women, a mother and two daughters at Evros border [northern border between Greece and Turkey]. And the issue that we try to open up femicide is another thing. And the femicide of refugees and immigrants is also one aspect of it, that is already a stigma in Greece, to talk about femicide [as a phenomenon recognized in this way], which is not recognized still. It is what feminists brought up as a term. But still the violence, the gender-based violence, although it is our daily lives, is not really named as this, especially in the media. And “femicides” for example, even the term, are not really much openly discussed.

For your information there are thirteen countries in Latin America, which have recognized femicide as a separate crime. Which of course can be talked about as well, if their process is really perfect or not is another question. And Spain and a lot of countries in Europe have recognized femicide, not as a separate crime yet, but at least in their official documents, like they have documentation [on it]. And it is very interesting that when I want to write about femicides in Greece I can use the statistics from Turkey, from Spain but not from Greece. The only thing I can tell is how many homicides of women have happened.

It is because in violence the gender aspect is not recognized, is not solved, is not understood and every time there is a brutal killing of a woman we are “in shock”. Because it is something that we cover up and when it comes to the public domain we are like “how could that even happen?”.

And the borders, the thing about borders is that all these femicides and this gender violence becomes even more visible because border is the mechanism actually that the gender violence escalates, upholds and continues.

And the borders, like we were talking about it, and as I was saying, if you asked me one adjective to describe borders I would call it masculine, in the sense that it serves the purpose of creating hierarchy. And it is fed on violence and it feeds violence. And the borders, when you look at borders: the biggest target is women, children, LGBTQI+ persons. So it [the border] creates these vulnerable groups and attacks them first. And think about all the journeys of refugees and immigrants of the sexual violence throughout these journeys. And so the femicide of three women next the Evros river is exactly because there is not a safe passage in the country where the states have created a very masculine understanding, targeting feminine subjects.

We were also discussing that it is not only the borders between nation and state, but also border politics exist not only within the journey [to Europe] but also afterwards, and in the camps. In the refugee camps –probably you have heard– about reports in Moria [camp in Lesvos island] there was a girl who was placed in the same tent as her rapist. And there are reports about rape and sexual harassment daily in the refugee camps. And then not only throughout the process of the camps, but also afterwards the borders and racism create new gender violence on immigrants and refugees.

Stella Nyanchama Okemwa:

Okay my name is Stella and I don’t speak Greek. I am from Belgium. And in Belgium I work for an organization called ‘Hand in Hand Against Racism’. But I am also a member of the European Network for People with African Descent [ENPAD] where I am a board member and also for other organizations. So I have been an activist since I was very very young and I have been an activist all my life. I volunteer and so on.

Based on what you have said… Europe, I come from Belgium but of course the Belgium reality might not be exactly the same as the Greek reality but we can make certain comparisons. For example in today’s world, not just in Belgium, not just in Greece, we are no longer just a diverse society. We have become super diverse which means that in certain areas of each country there are no majorities. There are many many minorities that make up a community. This means that we are more and more confronted with the ‘Other’. More and more confronted with new cultures, new ways of thinking, new ways of being, new people with new faces and so on. In other areas more than others they are confronted daily by incoming migrants or incoming newer faces… the gateway is here in Greece certainly, and in other areas of course. So the challenge is then that there is more and more exclusion ’cause every human being is compelled to protect their own. And I am talking about facism. I am just talking about basically if you have your family you want to protect your children. You want to protect your own family, the people you love.

The problem is when this need to protect your own becomes a need to put down the ‘Other’ you know… a need to hurt the ‘Other’, a need to exclude the ‘Other’, to make the other one less human, to have power over the ‘Other’. That becomes the problem and this is what we see more and more in today’s world and it is being used by more and more politicians for their populist ideas, for their fascist ideas and the whole energy is going over the world. Not just Europe, but we have seen for example in Brazil most recently and it is not going to stop there. In Belgium we just recently had elections and the rightest party did very very well you know. So the challenge is then to understand what are the roots of this exclusion. What are the roots of racism. Exclusion? Mmm, that is one way of putting it. We have to go deeper in to it… the roots of racism.

In my organization we identified that many of those roots of racism, exclusion or structural racism if I can put it that way, are rooted in the colonial project. During colonization there was a very systematic plan to completely degrade the colonized people denied and silenced of their culture for the good or for the profit of the colonials. Paradoxically the same mechanisms of propaganda, of brainwashing are also being applied here on the homeground. To make people feel superior, to feel that it is their right to own these colonial people. Their right to take property from them, their right to develop them. Their burden! You heard of the ‘white man’s burden’. Their burden to develop… Because first of all you must dehumanize them and then save them. So you dehumanize the colonized people and then you save them. But there were people here in the land of the colonials who were being brainwashed to learn how superior they are. How it is their god given right and might to rule over the people who are colonized and you know so on.

So my organization claims that we need to decolonize. We need to look those structures in the eye and identify them for what they are. Because the people who are in the colonized communities, who have migrated here, who are being structurally excluded from the society, from the host countries that they need to be aware of those structures that are putting them down so that we can start to address the issues. In the same way to the people who are here, who got privileges that they don’t even know, you know… They are enjoying privileges, which they are taking for granted like its their god given right. I am not… I don’t blame them. They have been born with it for generations and generations. But then when somebody busts that bubble and tells them “no no!”… If you and I go looking for a job, despite the fact that I got two masters you are likely to get that job because you got the right colour. You have got the right background, network and so on.

So in this way, right here people need to be unchained or freed from these structures that have given them this false sense of mind and power and authority. Without saying it you know it just happens in so many ways. I will get into that in a moment. Some of these ways are very subtle.

But it is a very broad concept so we broke it down into sectors. For example, we need… In my organization we have said we need to decolonize four sectors and that is our education, our cities, our tradition and our libraries. Most education systems are western oriented. Where you learn about how Christopher Columbus discovered and you know what I am talking about right? But it is not true. We have got students from all over the world who do not feel represented in their education. They don’t recognize their education, they are being taught, you are like who? I mean once living in that country before these white men discovered them or before discovered their… their mountain or whatever. So we need to decolonize our education. Look at our education system and make sure that it is more representative on all these histories that have been silenced. All these histories that have been denied, been ignored, that have been rewritten to suit certain western values. They need to be reviewed and rewritten again so that they can be representative of the people. But not only that. Even the teachers themselves, most of the teachers are very pale. They do not reflect the students. So we need to have a more diverse teaching core and we must find ways in which we can increase the number, the diversity in teaching. That is education.

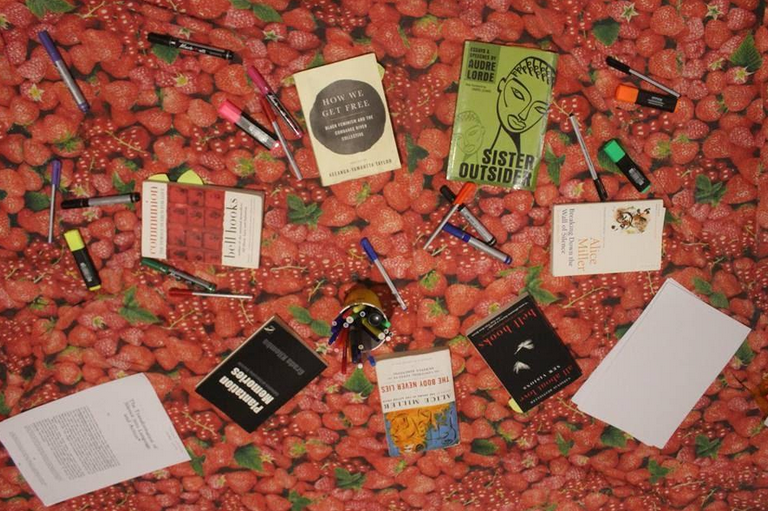

When we talk about libraries, a lot of our libraries have books again that are basically from western writers or western authors. If you want to have a book about a philosopher from Africa or from Asia or from a very little known community you have to go to some small corner of the library that has some specialized books from indigenous sectors of the world you know. And that is ridiculous you know! So libraries need to have books from all over, representing books so that people can have a honest view on what is available in the world. Besides that, books that are very colonial need to have an addendum that really contextualizes the time. Uncle Tom’s Cabin for example. This happened but it is not the reality from today. So we need to have in all those colonial books or books that praise the colonial time, or that praise slavery, we need to have an addendum in those books that says no, no. This was a period in XYZ but it is not the time we have now.

When we talk about our cities, many of our cities here are being presented as being very white. I mean Greek society if I look at the brochures is a pale society in the brochures. But then I look around in the streets… nah (negating)… it is not, you know. So we need to have what do you call it… A city has to be a microcosm of the society itself on all levels of the city. On the lowest levels to the highest levels. In the way that they publicize themselves. In the brochures and in the communication they give. Now the most… One of the most popular ways in which a city displays pride and its identity is in the names that they give their buildings, their streets, their monuments, in the names that they give their monuments. But how many monuments depict the diversity that is here? Sometimes some of the monuments have got colonial figures that are horrible, that are the horrible impact for some of the people who are now citizens of the society here. This is not acceptable! Every single citizen who is living here, working here, paying taxes here, has been accepted in this society deserves representation in all levels of the city: in the public spaces, in the politics, in the media, in the sports and so on and so forth.

When we talk about traditions, same old story. Okay if I can go back into something which Lauretta or I don’t know who brought that up is that in order to address all these issues you know some of those things have been festering for generations and generations without being articulated. Lauretta phrased it very well. The lack of spaces, safe spaces. I know from some people when migrants or people from African descent ask for space that is uniquely and exclusively for them, they receive it as a sort of “hä?”. That is racist, that is exclusionary you know. But then these communities have not had a time to regroup, to empower themselves, to give themselves the energy to communicate or articulate their problems. They have no space where they can speak about it even right here. If I look around they are… I have to be very careful on how I phrase myself because you don’t want to touch on the white fragility. (Laughter from the audience). You know, yes I am winding down. So there are so many areas in which I could talk about. I mean I am like… everybody calls me ‘Mamachama’ cause I have been an activist for so long. So they are so many areas in this topic that I could talk about but I will stop here and hope and pray that you can come up with questions which will enable me to deepen myself and get into certain issues that you might want to discuss.

Dolores:

I would just like to speak about AMOQA so we can close the first circle and open the discussion for all of us. I will tell a bit the story, how AMOQA started. It started in 2015. We were like a small group of people that we wanted a space that is of our own, that is queer, LGBT, non-fascist, non-capitalist, outside of the commercial fields, that was interested to work with art and theory and activism and work with what is happening with identities and all these power structures around us. It has been hard.

At the beginning, when we first wanted to start the space, it was very difficult because we didn’t have the money and the time and the energy to do it. The first step that did this space possible was to gain a grant that made it possible to create an accessible space, to have a rent covered for some months and be able to start. Since then the sustainability of the project has always been a problem. It happened in a time that also queer and feminist spaces were lacking in this city. And when we did AMOQA, it was one year after the closure of the feminist centre that was also a very long project that had to close due to the crisis and the lack of money. Depression!

Anyway, three years have passed, a lot of things have happened here and now we are facing the closure of the space because the building has been bought from an investment company that is something happening in Athens right now. Gentrification processes starting and the networks of the city are also changing, so apart of the crisis and financial problems, there is also another level of difficulties that we are going through and we have started facing.

What I also wanted to say from the beginning, it was that the aim of AMOQA, the initial idea apart from the space dedicated to culture and art as means to do politics, it was to be a platform meaning a space different groups can share and having not only one closed identity but a space that could be used from different people with different identities but OK a bit near politically, even if not in total. I am very glad of this event that happened here and thank you.

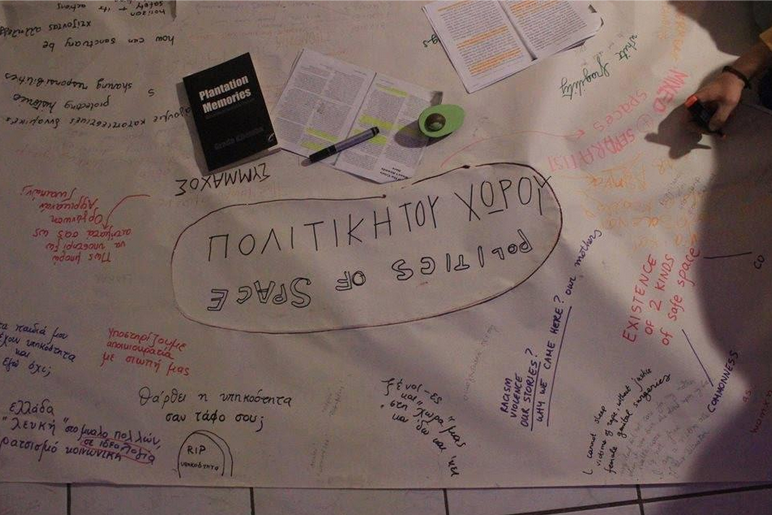

Can I say one last thing? Because you were talking about libraries and books and decolonizing the history, one of the projects of AMOQA was also to work and create an LGBTQ feminist archive that it is also a story to be re-written and talked about and be registered in Greece and of course the sustainability problems of space are also an obstacle when you try to do this kind of works. Because, no our archive is going to be in a house again, in a private space. It is very small and not very well worked or elaborated but once more will be private.

Stella Nyanchama Okemwa:

If we put one fragility warning for those that are not ready for such discussions. What more would you like to say on the topic, that you couldn’t before? Because you were afraid, how it would be received by the room.

Well, for one thing, Ι think white people do not understand the pain that we go through. The paralysis. They don’t understand the subtleties of the things. When people ask you: “how do you feel about that?”, “when are you going back to your country?”. There are very subtle things that we cannot express in mixed space. For example: talking about privileges or the fragility like I said earlier. When I would start to talk about, maybe the way I get excluded and some of the colonial atrocities that happened and the impact that they still continue to have upon me now and someone would say: “I had nothing to do with that… I mean, I don’t…”, and I am like: “it is not about you. And I don’t want, I don’t care about your apology. Because I am not talking about you. I am talking about me. Me”. And that is really hard to always keep on explaining that. Because it’s a very fragile and difficult topic. It’s about pain and emotion. And some things that are even too difficult to articulate. You want to reduce as many obstacles as possible. So, if we are in a space where I don’t have… I just open my mouth and you can feel it.

I was in one of those safe spaces and one of the participants had the talking stick. Because we were walking around with a talking stick. And she took the talking stick and she said nothing. And then she had these huge tears, rolled down her eyes. And we all understood exactly what she was going through. You know, you just know. It will not be the same dynamic, if you are in a mixed space. Its not like to diminish, that the other person is not having these feelings. No. They are. But in a different way. For example, when you talk about colorism. People who are not black-black but they’ve got mixed colors or they are paler. They’ve got other privileges. Even though they are black. They are considered black. But they are paler. So, they got privileges. So, in my other organisation, we have a session where we split up. The mixed people and the darker people. So, they can have their space. To also talk about their pain. To share the pain. The shared pain. You know. Many people are so terrified of silence or so uncomfortable with silence. But just even the silences, that we can feel it. You know, ’cause it can get lost in translation, in the mixed. That’s why I am saying, there is nothing. It is very good to be here. Please, don’t get me wrong. I love this. But it is also important to have the spaces as Lauretta mentioned. So, that we can just vent and get it all out. And not just that, but become enriched and empowered and feel that sense of belonging. And feel that sense of look at my back. And with that energy, we can embrace the other. We can be able to articulate our pain or dialogue with the other in a better way. But if you are dialogueing in a place of lack of agency and disempowerment, it’s very difficult to stand your ground and say “no”. And this hurts me and I want it to stop. Like what she says about being imprisoned. I learned from her. Because that is an expression which I understand immediately. But she articulated it. Things like that. I could go on and on but I don’t know if you understand what I am trying to say. You get it?

It’s like people who have been traumatized. And then they are in a circle with people who have been similarly traumatized. And sometimes you don’t have to say anything. Like mothers who ’ve lost their child. And again a group of other mothers who’ve lost their child. It’s… Sometimes you don’t need to talk. You know what I mean? That’s really more or less the same.

It’s an inversion of yourself in each person that is next to you.